Hello My Name is… Geddy Lee of Rush – talks about his “Effin’ Life”

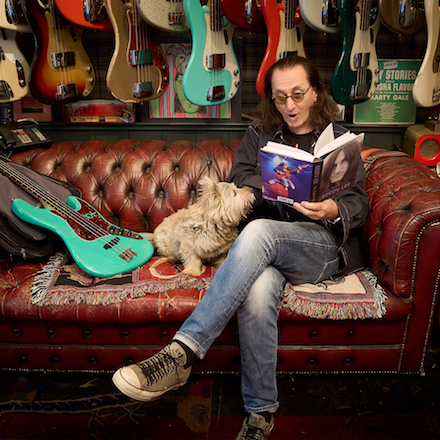

Rush bassist and frontman Geddy Lee makes it clear that the word “retirement” has no place in his vocabulary. Rush may be finished (or is it?), but Lee is a whirlwind of activity. His series for Paramount+, Geddy Lee Asks: Are Bass Players Human Too?, premieres on December 5 as an outgrowth of his best-selling Big Beautiful Book of Bass. He’s preparing for a major auction of baseball memorabilia from his stunning collection, opening on December 6 at Christie’s. His focus at this moment, however, is on the launch of his memoir My Effin’ Life and a speaking tour that visits the Auditorium Theatre in Chicago on December 3. The appearance will feature a conversation with a surprise guest host and audience Q&A. Hosts in other cities have included actors Paul Rudd and Eric McCormack, DJ Donna Halper, and noted showrunner/podcaster Brian Koppelman.

My Effin’ Life is not your run-of-the-mill rock memoir. True, Lee’s good-natured Canadian charm and self-deprecating wit are in ample supply. Yes, you’ll find chapters on Rush as a band of underdogs rising toward the breakout success of 1976 album 2112, victories including classic rock staple “Tom Sawyer” and 1981’s Moving Pictures, and final masterpiece Clockwork Angels.

Other portions of the book are poignant and powerful. Lee describes the challenges of growing up in Canada as a suburban Jewish kid in the ‘60s, drawing threads to relatable Rush songs, including “Subdivisions.” Lee describes the toll taken upon family life by his life with Rush and his devotion to his wife, Nancy Young, after weathering storms together. He writes movingly about the loss of close colleagues and family members, tragedies in the life of Rush’s beloved drummer and lyricist Neil Peart, and the devastating loss in 2020 of Peart himself due to brain cancer. One especially significant chapter tells the harrowing story of Lee’s parents Morris and Mary Weinrib, who survived the horrors of Nazi concentration camps during World War II.

Those darker passages provide context for the joy arising from Rush’s perseverance. Lee’s affection for Peart and guitarist/lifelong BFF Alex Lifeson is evident while chronicling the band’s ascent and the respected status that Rush gradually attained. There are tales of hijinks and lessons learned on the road. The book contains the story of quite an effin’ life, indeed. Lee spoke with Illinois Entertainer by phone during his tour’s opening week.

IE: For a memoir, My Effin’ Life is fairly comprehensive. What was it like diving into such a massive project?

GL: I’m sort of new to this writing business since 2018 when I started putting together the Big Beautiful Book of Bass. That was a very different kind of project because I was just describing and celebrating bass guitars from various periods. It was a nice way to find a bit of my own voice, being able to casually talk about those things while throwing in some stories from my own life. I had resisted the idea of doing a memoir for a long time because it seemed like it would be too all-consuming, in a sense of having me look backward instead of forwards. I’ve always run toward the light and not tried to reexamine the past.

A few things changed that. Number one was the loss of my dear friend and bandmate Neil after a terrible three-and-a-half-year struggle [with brain cancer]. Then, an ensuing pandemic, where I was sort of locked away with my reflections on that loss and desperately trying to put some perspective onto it. There was also the degeneration of my mother’s faculties. She suffered from dementia, and she was losing her memory. All those things were preying upon me. I was looking for some answers to help me regain my equilibrium and become more of my normal positive self.

After some spurring on from my good friend and co-writer Daniel Richler, I undertook the idea of looking backward with hopes that it would help me in a cathartic sense. And it certainly did.

IE: The book reminded me of what I had read about Rush albums. You and Alex and Neil would make the records for yourselves. The assumption was that if you liked the music, it would find its way to other people who also liked it. Did you take that approach for the book?

GL: In a sense, yeah. I didn’t really know how else to do it but to look back and scratch out my earliest memories and try to somehow put together a clear image for a reader of what it was like growing up in my neighborhood, what it was like living in my home, and the things that influenced me as a person.

I thought long and hard about the question, “What is the job of this kind of book?” Is it just to talk about your frolics, your adventures in rock and roll? I’m sure that’s what most people want, but I think it’s also important that the reader gets a sense of who this person is that they’ve seen on stage. What went into making this person behave and think the way they do? That required a little deeper digging and also being able to bare my soul and describe the conditions that I was raised under and the things that my parents went through, and all those things that contribute to making me the kind of human being I am. It was hard at times, but I felt it was important to do that.

IE: I would assume there’s a lot of value as a legacy for your family, too, even though I read elsewhere that Nancy said she would never read it [laughs].

GL: She’s still being obstinate about that [laughs]. It’s really funny because she started reading it, and then she realized it was the only copy of the book I had [at the time]. She freaked out. She said, “Oh, this should be under cellophane or something.” But there’s 25 copies sitting at my home right now, so she has no more excuses.

IE: I have to figure that Neil would’ve loved you joining him as a serial author and how much this memoir would’ve given you two to talk about. For so long, being a bookworm and writer seemed to be his territory among the three of you in Rush. Was it just as much of an outlet for you?

GL: He took to it naturally. He was a born writer. He was a born reader and philosopher. He had too many thoughts in his head not to write them down. I always had that wonderful expression of my instruments like guitar and bass and my screeching voice, where I could get out my inner angst and express my artistic goals. When that dried up due to my own decision in the aftermath of Rush’s disappearance, and of course, the difficulty of keeping Neil’s secret [about his cancer], which was his wish, I didn’t have a lot of joy.

Rock and roll should be a joyous expression. It’s also a collaborative expression, and I didn’t feel I was in a position to do that in the right way. Turning to writing words and expressing myself in that way was kind of a savior for me. It was a creative outlet. At the same time, it was a craft I was trying to learn. I’m very interested in being able to express myself as clearly and as precisely as I can. So, it was a great exercise for me to do. Along the way, I learned a lot about myself. I don’t think I came to it as naturally as Neil did, perhaps, but I seem to be starting to settle into it.

IE: The title would imply that you’re fond of the occasional F-bomb in everyday speech.

GL: Yes [laughs].

IE: I only ask this because it was so funny in my own experience – Do you recall the first time one of your kids dropped an F-bomb in front of you and Nancy? My own daughter practically set it up as a scientific experiment when she was four years old.

GL: Oh, really?

IE: She cornered us in the kitchen, where she could spot us both and gauge our reactions. She just let it fly.

GL: I think the first time I heard my son swear, he was swearing at me. I think I’d really pissed him off. He let one fly at me, and so I was shocked and amused. I used to say to him, “Well, listen, that’s okay. Sometimes, no other word will do.” I said, “Just be careful around your grandmother,” pretty much. But my daughter has never been that… Well, no, I take that back. She’s got a pretty foul mouth like me, now that I think about it [laughs].

IE: I think there’s real cultural value in you writing about your Jewish heritage at a time when fascism is back in the open, especially in recent years. Holocaust denial and antisemitism seem to be rising along with other hate crimes. Were those issues catalysts for what you wrote, or is that timeliness coincidental with simply telling an important part of your family’s history?

GL: I think it’s a bit of both. I always intended that if I ever wrote my story down, I would include a chapter about how my parents survived the Holocaust, which is how I came to exist. I’d done so many interviews with my mom, and we’d heard so many stories from her lips over the years. And it wasn’t just my mom. My uncles and aunts would tell stories to each other, and we would overhear them. Sometimes, they would tell us frightening stories that I don’t think we had any business hearing at such a tender age.

But I really wanted to set the record straight for my own family’s sake – for my children, my grandson now, and whoever may come after me. I’d like them to have a clear picture of how lucky we all are to still be on the planet. There was also a need for me to pay homage to my mother, who was very dear to me and who sacrificed so much in her life.

But in the back of my mind, yes, most definitely, I wanted to make a statement about the fact that this happened. There were eyewitnesses. There were victims that had testimony. Any denial of it has to be struck down has to be countered.

The fear that my mother always instilled in us was that it can and will happen again. In a sense, I’m thankful she’s not here at this moment to see how right she was. These things are on the rise. These hate crimes are now aimed at our people again, and we’re not the only ones that are victims of these hate crimes.

IE: Do you see cause for hope today?

GL: Of course, I’m hopeful. But if we’ve learned anything about the world in the last six to eight years, it’s that the world is not exactly how we wish it to be. There are factions that are trying to deny each other freedoms. That’s happening in civilized countries, and it’s happening in war-torn countries. It’s happening right now in the Middle East. There are a lot of people on both sides of this horrible conflict that are suffering in it. It’s a terrible thing to witness.

IE: The statement released on Rush’s Instagram expressed outrage over the intentional deaths of Jewish civilians during the October 7 attack while extending sympathy to innocent Palestinians in Gaza. Public reactions since then have been polarizing. It often seems like there’s a willingness to condemn military reprisals while not necessarily condemning terrorism.

GL: Hate crimes are happening all over the place now. There’s no room in the world for that. I saw a wonderful comment that somebody [author Hen Mazzig] posted the other day: “Both Israelis and Palestinians deserve safety, freedom, and dignity. That’s not hate speech. Opposing any part of this sentence is.” I thought that really hit the nail on the head.

IE: Your mother clearly saw your success with Rush as a victory for the family, especially after what she and your father suffered. It was funny but sad that your grandmother didn’t quite see it that way when you and Alex were headed to the basement to make a racket as kids.

GL: It was touch and go there for a while. My poor household, my poor grandmother. She thought after my dad had left us, we were getting wilder and wilder. At the time, I didn’t fully appreciate how stressful that must have been for my mom and my grandmother. Of course, they couldn’t possibly understand these cultural changes that were happening. We were teenagers, so it was really nuts at times, and their reactions were very strong.

IE: I vividly remember first hearing “Red Sector A” in 1984 because Grace Under Pressure was my first brand-new Rush album. The sound was so cool, but the song was chilling. The horror went beyond fictional storytelling. It felt personal and had gravity.

GL: That song started out innocently enough because the section we were given to stand in while watching the first launch of the Space Shuttle was called Red Sector A. That’s where Neil got the name, but the story had nothing to do with that. It really was inspired by conversations Neil and I had about my mother’s last few hours before and during her liberation [from a Nazi concentration camp] in 1945. They had all given up hope that civilization had survived because otherwise, why wouldn’t someone come and save them or let them free? So, they were shocked when they saw the German soldiers with both hands in the air. They just interpreted that as a new kind of Hitlerian salute [laughs]. But there she was, free. It was hard to take in, I think.

IE: It must have been a staggering moment. I’m sure you’re familiar with Between Two Ferns with Zach Galifianakis. Have you seen the episode with your pal [and opening night host] Paul Rudd?

GL: Yes, I have [laughs].

IE: My favorite quote is when Galifianakis asks, “Are you practicing?”

GL: Yes [laughs].

IE: And Rudd responds, “No, I’m not a practicing Jew. I’ve perfected it.”

GL: That’s right [laughs]. What can I say? He’s one of my heroes. I love that guy. You don’t often find a movie star that popular who has his head screwed on right. That guy most definitely does.

IE: I hope to find some clips online from Monday’s show to hear your conversation with him.

GL: It was wonderful, it really was.

IE: What’s your favorite Yiddish insult, either the most devastating or the one that made you laugh the hardest when you first heard it?

GL: They all make me laugh. Somewhere, I have a book that has a list of Yiddish insults, and I’m just shocked how gruesome they are when you translate them to English. And yet, they’re used so flippantly in the most banal situations. There’s one that I’ve always been fond of that goes, “Zol dayn oygn aroyskrikhn fun dayn kop,” which means, “May your eyes crawl out of your head.” I mean, who says that to someone else?

IE: You described a safer but stifling suburban childhood and connections to songs like “The Necromancer” and especially “Subdivisions.” “Middletown Dreams” reflects on the desire to escape small-town ennui. Does Rush music appeal disproportionately to people with those sorts of backgrounds?

GL: I do think that there’s a strong connection with other people that live in the suburbs or in those situations where they somehow feel themselves to be uncool or disconnected or somehow on the fringe of hipness.

That’s what those songs kind of speak to, but Neil was a real lover of small-town life. Part of the reason he enjoyed traveling by motorcycle and bicycle on his own pace was that he could stop in a small town in America and he could go anonymously into a cafe and strike up a conversation with a waitress or the person in the booth next to him without fear of being outed as a celebrity.

To me, it showed how much of a human he really was. Although he’s portrayed as being distant and the whole “Limelight” thing [with the lyric, “I can’t pretend a stranger is a long-awaited friend”], it’s all context. With “Limelight,” he was talking about fame. In his everyday life, he liked nothing more than to meet everyday people. That’s reflected in numerous songs that he wrote.

IE: You admitted to being Mr. Bossypants in the studio while trying to make the perfect record. [2002’s] Vapor Trails has a few of my favorite Rush songs, including “Secret Touch,” “Ceiling Unlimited,” and “Earthshine.” Clearly, though, making that album was a rough time that left a bad taste. You didn’t say whether [2013’s] Vapor Trails Remixed redeemed much of that experience. Did it?

GL: Yes, it did. Don’t get me wrong, I’m very proud of the songs we wrote on that album. It was a monumental task and a very delicate process because of all the reasons I explained in the book and what Neil was trying to rebound from [after losing his wife and daughter]. The way it ended, I felt very disappointed that I’d let our fans down. I’d let our standards down by being too burnt out and unobjective about things right when you really need to be the most clear-headed. So, yes, it was vindication to have David Bottrill remix that record. I think he did a great job. I just wish it had happened much sooner.

IE: I was eager to read chapters on the albums between Signals and Hold Your Fire. That was when I came into the fold. The first I remember hearing about Alex’s beef with the shift toward the keyboard-friendly arrangements on those albums was probably related to retrospective questions about Signals. There’s no shortage of cool guitar parts on that record. Do you think a different guitar-forward mix would’ve scratched his itch back then, or was it more to do with fighting for space as the top-line instrument?

GL: It’s hard to say because at the time, he didn’t object to where we were going. During the making and recording of Signals, he really never spoke up to say, “This direction isn’t for me.” That was never said by him. So, we just assumed that we were still all for one, one for all, and we’re just trying something a little different. I think when the record was finished, he started getting a bit grumbly about it. When he was able to listen to it objectively and see how his sound and role had shifted, I think he was unhappy about that.

So, that was sitting in the back of his mind when we moved deeper into these more elaborate keyboard records. I think when Peter Collins came in to produce us and brought in outside keyboard help, that really pushed [Alex] against the wall. My regret now is that I wasn’t sensitive enough to it. I was so excited by it that I just assumed he was, too. Obviously, he wasn’t. Being the company man Al is, he just sucked up all this resentment and did it. It wasn’t until years later that I really discovered what a dickhead I had been in some ways toward his needs and his feelings.

IE: Your close friendship may have worked for you and against you in that situation.

GL: I guess. At the same time, we’re still besties, so it’s all good.

IE: Your commentary about “Freewill” made an important distinction between holding true to one’s values and the responsibility of participating in a functioning society. Being decent to others should be considered virtuous. Does that conflict with any part of the song’s message?

GL: Even though someone could interpret it as being at odds, I don’t think it is because that song was not written out of cruelty. What we used to talk about in Rush, and what Neil used to espouse, was that the only crime is cruelty. If you choose an independent life, if you choose to ignore society to a certain degree, that’s your business. But when it comes to the point of threatening the health and safety, and even goodwill of your community, then you’re bordering on a cruel act. I don’t think there’s room in society for cruelty. Unfortunately, we’re seeing cruelty being paraded as a virtue all around the world. I think we’ve all had enough of that.

IE: I did appreciate your quote in the book, “I prefer to live in a world that gives a shit.”

GL: I couldn’t have said it better myself [laughs].

IE: You wrote about the difficulty of recording “Tom Sawyer” for Moving Pictures, wondering at the time whether it was worth the grief it was causing. You thought about dropping it and could have conceivably gotten your way. Who convinced you that you’d lost your mind?

GL: [laughs] Our engineer Paul Northfield saved that song for me. When he came through with that amazing guitar solo sound, it changed the way I viewed the song. Of course, I never had an idea that it would be as popular as it became. As the mixes came together, it was clear that [“Tom Sawyer”] was a very strong song to open the album. But I was pretty down in the dumps about it for quite a while.

IE: Maybe you thought you had the bases covered with “Limelight” as a single at that point?

GL: Well, I liked everything else on the record. It’s just that everything to do with “Tom Sawyer” was difficult. It was just one of those songs. That doesn’t mean that there’s something wrong with the song. But after a while, you start to wonder, is it worth all the trouble? Should you maybe just move on?

IE: In an alternate universe where Grace Under Pressure might’ve been produced by Steve Lillywhite or Peter Collins, or Terry Brown, how differently do you think it would’ve turned out? Did that arduous experience still result in the record that you really wanted to make?

GL: Of course, it would’ve turned out differently. I mean, you have someone in the studio with you that influences the end result. No question it would’ve been a different record. Would it have been a better record? No one can say. When we finished that record, as difficult as it was to make, I was really proud of it. But I couldn’t be objective about it because it was such a motherfucker to get finished [laughs].

IE: While reading about the tough ones like Vapor Trails or Grace Under Pressure, or Hemispheres, it was fun to read about the happy experiences, too. I think you said that Snakes and Arrows was smooth sailing. You knew you’d done good work and were glad to send that into the world.

GL: Snakes and Arrows was one of greatest recording experiences we’d ever had. Completely the opposite of Grace Under Pressure.

IE: You’ve singled out “The Garden” from Clockwork Angels as your own favorite Rush track. Why?

GL: There’s just so much of it that reflects the wisdom of a life lived. “The fullness of time” is such a beautiful concept and a mature concept. That’s not a line you can sing when you’re 21 years old because you have no fucking idea what the fullness of time brings or means.

I think when I say “The Garden” is my favorite song, certainly it’s one of my favorite songs. I say that from the perspective of a person of this age, and I say that because I appreciate the hard-fought experience and wisdom that is on display in that song about looking for the meaning of life – the fruitless search for the meaning of life, where it may bring you, and when it can bring you some peace. So, those are the things I love about that song.

IE: Shifting topics to baseball: There are amazing items at the Christie’s site in your upcoming memorabilia auction. I spotted signatures by Babe Ruth, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, Jackie Robinson, Rube Waddell, astronauts, presidents, and more. I was floored by the fully autographed Beatles baseball from 1965 at Shea Stadium. After being such a dedicated collector, how can you part with such important pieces?

GL: Collecting is a younger person’s game. As you get older, you’re trying to simplify your life, not complicate it even more. I’m very bad at that. I appear to have really complicated a part of my life that should be much simpler than it is, but that’s my nature.

I have so many baseballs, so many wonderful memories tied up in there. A number of years ago, the fellow who I built my collection with passed on. I really have not bought a significant item [since then]. I’ve added things to my collection, but they’re mostly gifts from good friends that are in baseball or players. I would never sell any of those.

Collections need to be fed, and I was no longer tending to my baseball collection. I was busy buying bass guitars and learning about vintage instruments. I have so many things that I want to do, that I want to learn, and I had let my baseball memorabilia sort of get dusty. So, I just thought, nothing lasts forever. We’re just a custodian of these things until we pass them to the next custodian. Let me give a gift to all the collectors out there. Let’s make these things available that have not been on the market for years and [let the collectors] have at it. I have no regrets about it. I still have a huge collection of baseball ephemera that has meaning to me. Some of them are very personal. I kept some wonderful things.

IE: What’s an example of a ball that’ll never leave your house?

GL: I have a ball from Roy Halladay’s no-hitter that I would never sell. He was my favorite pitcher. I have a ball from [Toronto Blue Jays pitcher] Dave Stieb’s no-hitter. He’s a dear friend; I would never sell that. I have a ball that Randy Johnson gave me from his 300th win. I have the great Bill Lee’s uniform that after his friend Rodney Scott was traded from the Expos, he took it off in the locker room and tore it in half in disgust and then marched across the street to the local bar where he quaffed an inordinate number of beers. I was able to purchase that from the Expos manager at the time, Jim Fanning, who was a lovely man. I became friendly with the Fanning family, so I can’t part with that. All my Blue Jays stuff I’m keeping for my grandson. So, I’m not bereft of wonderful baseball articles or memories. I can happily move these [other] things on to someone who will be very excited.

IE: When we talked about your Big Beautiful Book of Bass, I asked whether you might write a book on baseball collecting. You said there were already so many books about baseball history that you didn’t know how you’d add something fresh. Did you find a way?

GL: Well, frankly, I did do a book because I have so much spare time [laughs]. It’s a collection of stories from some of my favorite items in my collection. Maybe I’ll release it on opening day next year, I don’t know. I’m going to include a copy of the book to the winning bidders of those particular items in my sale that are also featured in this book. I’ll give them a signed copy. [The book] came together in a relatively painless way. I wrote it with my co-writer, Daniel Richler. Richard Sibbald, who shot the Big Beautiful Book of Bass, took the photographs. They’re absolutely stunning.

IE: You told me before that he had really wanted to do that.

GL: Yeah, he really did. He was bugging me forever to shoot some of the baseballs. So, there is a book, and I’m really pleased with it. I’m trying to get it printed now, in time for the auction. It’s called 72 Stories from the Collection of Geddy Lee.

IE: Did you ever find the pre-CBS foam green Fender Jazz bass or the blue floral Telecaster bass you were hunting when we spoke about the bass book?

GL: I have the blue floral Tele bass, yes. I have a pre-CBS foam green Fender Precision, but I don’t have an authentic pre-CBS foam green Jazz bass yet. So, I’m still looking.

IE: How did you find the blue floral?

GL: It was wonderful story. A young bass player wrote me on Instagram. I don’t respond a lot to Instagram DMs, but something about this kid caught my eye, so I read his message. He was at one of my talks, and he heard me talking about that bass. He took it on himself to be obsessed with finding me a blue floral, and indeed, he did! He found a guy who had one for sale on Kijiji or something like that. He turned me onto it, and what do you know? We ended up making a deal for it. It’s in great condition, and it’s just a wonderful addition.

I’m still sort of in contact with that young man, and I thanked him for it profusely. There was a bass he wanted, and I was able to locate one for him. I think I’m going to actually meet him at one of the gigs coming up.

IE: When did this happen?

GL: I think it was about three years ago. I think it was just before the pandemic.

IE: When your book tour nears its conclusion, your TV series Geddy Lee Asks: Are Bass Players Human Too? will launch. That casts you back in the interviewer role you had when talking to noteworthy folks for the Big Beautiful Book of Bass, and it incorporates your love of travel. That sounds fun, and I have to imagine four episodes won’t be the end of it.

GL: We’ll see where life takes me. I didn’t expect to have so much fun doing it. When we finalized that idea, I honestly put it out of my mind because I didn’t think anyone would really want to make such a strange show. It appears I was wrong, so then I had to go do it. I had a great time. I had to learn how to be the guy on the other side of the camera. That was a challenge, and I really like doing things I haven’t done before. I like breaking ground. It’s what makes life interesting.

IE: It must be good to have your brother Allan [Weinrib] to work with as an experienced filmmaker.

GL: Oh, absolutely. He’s great. He’s helped me with the book tour as well. He’s been a part of my life – obviously as a family member, but we worked together for years on all the Rush videos and films. He was an important part of the Rush team certainly in the last 10, 15 years of Rush’s existence. So, when it was time for me to do a book tour, I called on him to help. He was terrific to work with, as always. We did this [TV] show together, too, so that was nice.

IE: I liked reading anecdotes in My Effin’ Life, where the leading heavy rock and prog bassist talks about his love for artists like Aretha Franklin and The Supremes. That appreciation for R&B and soul music was also reflected in your bass book. Is there a Rush bass bassline that reveals any influence by James Jamerson or Bob Babbitt?

GL: Oh, God, that’s a good question. I don’t really know. I don’t think I could be objective enough about my basslines …

IE: It’s just in there someplace?

GL: It’s just in the mix. It’s in the stew that cooks along in my soul and then comes out through the ends of my fingers, according to the requirements of the song I’m writing [laughs].

IE: Quick answers: favorite Beatles song?

GL: “Taxman.”

IE: The Who?

GL: “Won’t Get Fooled Again.”

IE: Led Zeppelin?

GL: Maybe “Kashmir.”

IE: Cream?

GL: Too many. “White Room.”

IE: Yes?

GL: “Heart of the Sunrise.”

IE: Genesis?

GL: Oh, God. Again, too many. “Watcher of the Skies.”

IE: The Tragically Hip?

GL: Road Apples.

IE: Max Webster?

GL: “In Context of the Moon.”

IE: Rush’s presence was so positive. To fans of rock music, you were Canada’s greatest ambassadors. What allowed Rush to reach people in the United States when other great Canadian bands like The Tragically Hip or Max Webster couldn’t crack it open? I was late to both of those bands because there was no exposure to them where I lived.

GL: Well, I think you just answered your own question. There was no exposure to them. We stayed in the United States, touring endlessly, opening for any band we could, getting in front of people. We built our following through a groundswell and the good vibes from being an opening act. That was ‘74, ‘75, ‘76 – three years of nonstop touring and opening for other bands, putting ourselves in front of the good people of the Midwest largely, who created a following for us. As you said, it’s exposure. I think that’s all it is.

IE: When you first read a description of your singing voice described as something like “the damned howling in Hades,” were you tough enough to say, “Those squares just don’t get it?”

GL: When I was young, it was easy to slough it off because that’s just the nature of youth. You know, “Fuck that guy.” You carry on. There was not much I was going to do about it; you sound like you sound. I was quite happy with our sound, and so were my partners, so that was fine. But over the years, I have tried to learn about using my voice in other ways. I’ve tried to shape my voice and become a better singer and a more versatile singer. Criticism has its place in every art form. I don’t disregard [the critics] just because I don’t like them or because they might be a little hurtful. At the same time, you have to take everything with a grain of salt, including the effusive reviews. If somebody’s raving about our music, I can distrust it as much as when they slag me.

IE: I like the thought that the guy who sang “Finding My Way” is the same guy who sang “The Garden.”

GL: That’s a nice comparison.

I listened to the whole of that last record [Clockwork Angels] not long ago. Right from the beginning, Neil thought that was our greatest piece of work. I think in a sense, that really did send a signal to his brain saying, “I can’t beat this. Maybe it’s time to stop.” I would like to have had the chance to beat it. So, I came around to [Neil’s way of] thinking only after it was evident there would be no more records.

IE: Neil did seem to wholly embrace retirement. Still, the book includes an email from him saying, “Maybe someday – never say never – but not now.” What do you suppose he meant?

GL: I think that meant that in his current state of mind, Neil was doing exactly what he needed to do. He was home with his young daughter and trying to be a figure in her life, and there was no way on earth that would shift anytime soon. But he was also wise enough to know that things change, feelings change. Who knows? A year or two from now, he may find that he satisfied [those priorities] and he’s got a comfortable home life. Perhaps he’ll get the itch to hang out with his two idiot pals and make some music together again. I thought it was a very hopeful thing.

IE: Last year, you and Alex were introduced as Rush when you joined your friends in Foo Fighters for the Taylor Hawkins tribute concerts in London and Los Angeles. You honored Taylor’s memory and also honored Neil’s memory. Apparently, an actual Beatle told you that you ought to continue. How did that conversation with Paul McCartney go?

GL: Paul was just effusive and generous and kind. From the minute we were at rehearsals in London, he wanted to say hello to us. It’s not because he knew our music; it’s because I think so many people had bugged him, saying, “Have you heard [Rush’s] music?” I think he had a great curiosity about us, I think. Being very close with Dave [Grohl], he probably heard Dave talk about us.

When we did meet, I was so blown away by his candor and his positivity. During the show, I guess he stood beside the stage to watch us. He’d been listening to us at rehearsal through the halls, but he came and watched the set, and I guess he just loved it. He never said so, but I am assuming that by his reaction when I came off the stage. He was backstage with us, and we were having such a great time chatting. He was very warm.

When we finally got to relax with all the artists in the bowels of Wembley [Stadium] at the bar, and we were sharing a drink together, he just looked at me and said, [in McCartney’s accent] “Well, you have to go on the road. You’re going to do that, right?” I said, “Well, my partner there, Alex, isn’t sure.” He said, “He’s not?” And then he just went over to Alex and said, “D’you know what Ringo says? It’s what we do.” And Alex started joking around to him and said, “Well, yeah, okay. I’ll go on the road if you’ll be my manager.”

And Paul started laughing. He said, “Yeah, sure, I’ll do that.” And then Alex said, “And if you’ll be our caterer, too.” It was just a lovely gesture. It was unprovoked, and [McCartney] was just sharing what he really felt from his heart. He just thought we should keep doing it. I appreciated that.

IE: Have you and Alex gotten together to work on songwriting a bit?

GL: Well, we haven’t done it recently because I have this thing called a book and a book tour. So, Alex is a little peeved at me right now because I’m so effin’ busy with My Effin’ Life. But yeah, about a year ago, we got together just to have coffee and shoot the shit. Naturally, we went down to my studio, where I had not spent a lot of time since Neil died. It had always felt a bit claustrophobic to me.

So, we got down there, and there was Big Al. He sat in his seat, and there were his glasses left exactly where he had left them when we finished writing Clockwork Angels, believe it or not. He picked them up, and they still worked.

We started messing about and jamming together. In a few minutes, I was already bossing him around. “Wait, why don’t you try this note here?” We just started laughing. We left everything we recorded on tape, and I didn’t look at it again. We walked away, knowing that that’s something we should do at one point in the future. We’re still waiting for that point. I hope that in the coming year, we’ll make that happen.

Geddy Lee appears at the Auditorium Theatre on December 3, 2023

– Jeff Elbel

Thanks to Meg Symsyk for making arrangements. Thanks to Eddy Portnoy for help with Yiddish.

Links:

Geddy Lee Asks: Are Bass Players Human Too? on Paramount+

Selections from the Geddy Lee Collection and Important Baseball Memorabilia at Christie’s

Category: Featured, Hello My Name Is, Hello My Name Is, Monthly