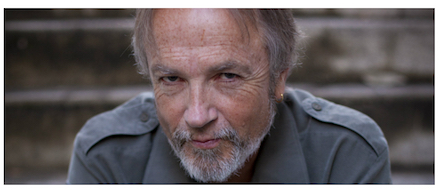

Cover Story: Steve Kilbey

Serenity is where you find it; Steve Kilbey has decided, mid-pandemic. And in his beachside home in gorgeous Sydney, Australia, it’s something that the spiritual-minded Church frontman has been actively seeking, from the moment he awakens every potentially-oppressive day. First of all, he says, “I have to be near the sea, I need to see it — I always have. I need the ocean on an almost cellular level because it’s so powerful that you can actually feel it in the air. So I know solace every day, no matter what’s happening in the outside world, because the ocean changes everything.” Ergo, during an average Down Under day — seven recent ones of which he spent spontaneously writing and recording a brand-new solo set, Eleven Women, which jangles like the best of his vigorous ‘80s Church work (including their moody anthem “Under The Milky Way”) — the singer takes regular swims in the Pacific but prefers dog-paddling through local sea pools, extensions of coastal tidal pools that are always relaxing. And he always wears a diving mask so he can spot every alien marine visitor. “There are so many sea pools in Sydney, and in my neighborhood alone, there are four,” he reveals. “They fill up and empty with the tide, and my particular pool is full of fish, octopi, birds diving in and out, and sea slugs, which are actually quite lovely creatures.” Don’t even get him started on the occasional jellyfish, some with stinging tentacles, like the Bluebottle, some not — eternal vigilance is the price you pay for a daring dip.

Usually, Kilbey has few spare moments. To date, he has: filed over 750 songs with APRA (the Australasian Performing Right Association); formed seven side projects, including Jack Frost with the late Grant McLennan from The Go-Betweens; been inducted in 2011 into the Australian Songwriters Hall of Fame; penned an autobiography, poetry books and designed his own set of Tarot cards; exhibited his paintings in several posh galleries; and spent every Monday since the coronavirus clampdown broadcasting live home concerts via Instagram. But he somehow found a week to squeeze in the eleven chiming female-themed charmers that comprise the new record, including the off-kilter-chorded “Poppy Byron,” a John Lennon-ish “Woman Number Nine,” a minstrel-folksy “Josephine,” and the Phil Spector-thick “Birdeen,” an ode to a lorikeet that frequents his bird feeder. It’s a gossamer, ear-candied affair, the perfect delightful distraction from the 24-hour right-versus-left TV news juggernaut that’s bearing down on America as this crucial election looms. What does this usually-outspoken rocker think of how close humanity has come to the brink of its own extinction? He chuckles mischievously. “Well, don’t you think that when pop singers talk about stuff like this that it trivializes them?” he asks, rhetorically. “Don’t you think that people come to pop singers so that they WON’T talk about the end of the world? Hoping that they will just talk about their latest guitar solo or something?” Naturally, he’s not interested in discussing his latest guitar solo….

IE: In an era when such a ridiculously low percentage of Americans even owns a passport, the input of educated, world-traveled musicians should never be discounted. They’ve looked at our country from outside in and inside out and can relate the truth to us with a certain degree of objectivity. And we should listen.

STEVE KILBEY: Yes, so I can speak freely. But I just don’t know if anyone wants to hear me saying the same things about climate change that everyone else says. Like, what did we expect? Look, I went and saw the new David Attenborough film the other day, and I just started crying as soon as it started, just watching the rain forest go down, and watching one orangutan find just one tree where there used to be miles of jungle. There’s one tree with one orangutan sitting up in it, eating the one leaf that’s left on the one tree. It’s like, What the fuck have we done? And it also makes me feel glad that I’m old. I’m 66, and I’m not going to live long enough to see it crawl to its ultimate conclusion, so I’m kind of glad that I’m opting out. I look back on my teenage years in the ‘60s and ‘70s and talk about halcyon! It just seemed like everything was great then, and I didn’t even hear the word ‘pollution’ until the late ‘60s — no one was even talking about it. And, as David Attenborough said, he always imagined that the world was infinite. And now we’re finding out that it isn’t, and it’s really come to the end of the line, and it can’t renew itself anymore. And you know, the right-wing press in Sydney still denies it, saying we should still keep mining for coal and using fossil-fuel cars. They’re still trying to find statistics to prove that it isn’t happening. I watched 12 Monkeys the other day — re-watched it with someone who hadn’t seen it — and it totally resonated. It’s a great movie, and it still holds up. But one way to respond to this is something I’ve been banging on about for a long time — everyone has to become a vegetarian or a vegan. Yesterday. We can’t eat meat anymore. It’s finished — it’s not a sustainable future. But I can’t see it happening. People are too fucked up. And if there’s still one more fish in that sea, someone’s going to be out there, trying to catch it.

IE: Speaking of fish — and to lighten the mood a bit — what is the strangest creature that’s appeared in your sea pool?

SK: Well, it was a bit of a tourist attraction for a while. But my pool had a rather large blue grouper, and this one was as big as a person. It was at the bottom of the pool, and for a while, people thought it was sick. But it was actually just lying on the bottom so all the little fish would clean it, eat whatever it had on it, all the algae and stuff. And then the pool got very used to having it, and they even printed up T-shirts saying, “Come and see our grouper!” And then one day the bastard got out and just swam off! But that was pretty strange, seeing that big fish in there. But he was pretty lazy. But sometimes I’ve swum up and down the pool, and I feel like some of the fish are escorting me. I think they’re bream, but they actually swim along with you because the fish get so habituated to humans that they’re not frightened anymore. It’s a really beautiful thing. It always makes me think that this is the way that life was supposed to be, where everything wasn’t scared of human beings because it’s really amazing to get in the pool and the fish don’t swim away — they know that they’re safe and protected.

IE: Besides aquatic activities, how else do you pass the time?

SK: Well, everything changed, obviously, with COVID-19, because normally I’m touring. So without touring, I’ve been playing a lot more acoustic guitar, I’ve been writing a lot more songs. And I do Monday live shows from home. And I do a lot of walking — try to walk five or six miles every day; I do a bit of painting, I smoke a bit of dope. So I’m taking it easy, I guess.

IE: Your portraits are very Modigliani-sh.

SK: Yeah. ‘Why the long face?’ Yes. Thank you. But with portraits, when you think about it, if someone goes away on holiday and takes loads of pictures of the Taj Mahal or the desert or the ocean and stuff, you always want to see a human in it, as well. Humans just like to see humans, and I think the most interesting thing is the human face. And it’s strange when you start painting — you look at a face, and you want to paint it one way, but then you keep looking at it, and you realize that it isn’t like that. And then you sort of have an argument with your eyes because faces are very surprising. It’s also very hard to detach yourself when you’re looking at a face, to see what you’re really looking at. I read one book, when I first started painting a long time ago, that said, “If you want to paint a good painting of a face, turn it upside down. Then you can do it with no attachment because when you’re looking at a picture of a face, your eyes sort of lie to you about what you’re seeing.” So they’re very hard to do, and there’s more at stake — if you’re painting a tree and you don’t get it right, no one will care. But if someone hires you to paint their portrait, and you can’t capture their face, they’re gonna know it. So it’s definitely more of a challenge. And the Australian government has just doubled the price of art degrees — they’ve doubled them to make them prohibitive because they don’t want people to do them. They want people doing degrees in the humanities, people doing degrees in useful subjects like accounting and business and stuff like that. But that’s where we’re at. So it is fun being an old guy and knowing you’re gonna die soon, going, “Wow. You guys are really gonna reap what you sow if you turn out a nation of accountants and businessmen, and you ignore the humanities.” Like in England, where they’ve been telling all of the musicians to retrain because there are no more jobs for musicians. Especially the choirs — choirs have really been hit hard. The very act of singing emits a lot of potential COVID [germs], so choirs have really been cracked down on. So they’re saying that 80% of all the people in the music business have to go and find another job in England, and they’re doing little posters where they suggest, “Oh, he didn’t know that he might be a good castle tour guide!” Can you imagine that? You’ve studied cello your whole life, and in 2021 they tell you, “Look, there are no more jobs for cello players. But we’ve got a nice job for you guiding people around this castle in Scotland!” Can you imagine that?

IE: Where did this album originate? As an aesthetic eye for female beauty, inner and outer? And was it written pre- or mid-pandemic?

SK: Look, the truth is that a long time ago, one day I was having a stoned conversation with someone, as you do, and I said, “Gee — imagine an album where every song is about a woman, like looking at a photo album, but instead of a photo album, each song is a woman.” And I guess I filed that idea away in my head for years and years. But I was learning to play Church songs in their entirety for my Monday night shows so that I could play all the sounds in their entirety. And then I sort of realized that I was spending a lot of trying to figure out those songs, what their chords were, and how they fit together. And, like with “Unguarded Moment,” you can’t really, now can you? You’ve got to do what you can, and I’ve got a 12-string guitar, so that helps a little bit and can give you a bit more bang for your buck. But I thought to myself, “It would be easier to write a brand-new album than to go back and keep learning these old ones — it would actually be less work and less practice.” So one day, I said, “I’m gonna do a new album, and I’ll have it ready in one week.” And that was probably about ten weeks into COVID. So then I raced back through my old mental notes and found this idea about every song being a woman, and I thought, “Well, I’ll just get that out.” And I wrote the album in a week.

IE: And it’s really great. But most importantly, your voice is virtually undiminished.

SK: I like that word. Thank you.

IE: What is, say, “Poppy Byron” about? And lines like “Mary Shelley/Was watching the telly”?

SK: Hey, she would’ve! If she could’ve! I like the archetype of a sort of poetry girl — I like the idea of a Poppy Byron, who embodies all that sort of poetry stuff from those days, the days of the great English poets. And I like the idea that somehow she survived and she’s still amongst us, and it would be nice to have a little song about her. These songs are whimsical, like when you fall asleep, and you go into the hypnagogic stage. There’s a stage between being awake and being asleep, and it’s called the hypnagogic stage. And that’s what I’m trying to make my songs like — they’re like thoughts you’re having as you’re falling asleep. It’s like they’re no longer thoughts, but they haven’t yet turned into dreams, just like little imaginings, reveries, or daydreams, little ideas floating pas that don’t have any substance or any reality to them. I’m trying to do that with a song, trying to capture that liquid stage where anything can happen. My favorite songwriters that I always bang on about, like Marc Bolan and David Bowie — they had that in their songs. They had this fluidity that you didn’t question because it was in a song. I think songs and poems are the only things that can do this — just follow the fluidity of the human mind as it jumps from subject to subject. I’ve got a friend, and every time I have a conversation with him, he’ll just jump from subject to subject to subject. And I like that idea, and I like the fact that your mind can do that. So that’s what all these songs are — they’re the fluidity of a human mind in full swing, backed up with music. Poppy Byron can do anything she likes because she’s just a character in a song, and you don’t really know much about her.

IE: Is “Woman Number Nine” a reference to Patrick McGoohan’s The Prisoner?

SK: No, but it could be! “I am not a number; I am a free man!” I did another interview with an American writer, and I said, “I’m the kind of guy that — because I have so little regard for mathematics — I do Song Number Two for the album, and I call it ‘Woman Number Nine.’” And this guy started laughing and said, “Well, Steve — you’re still sticking it to the man!” Which I thought was funny.

IE: But “Birdeen” is an actual lorikeet?

SK: Yeah. “Birdeen” is a lorikeet, and she turns up here every day. You don’t have lorikeets in America, do you? She and her husband turn up here every day, and they’re kind of strange creatures. But I’m in sort of a relationship with them now, because they turn up and they like music. They did a bit of a deal, I think, with God, because they’re the most beautiful birds, but their voices are just terrible. They can’t carry a tune. But then you look at a lark, and it’s kind of a very dull and boring-looking bird, but it can sing beautifully. I mean, Birdeen’s dressed up like she’s going to a bloody debutante ball, and yet she can’t sing at all — she just makes this horrible squawking sound. But she really likes music, and she really likes honey. And she sort of just turns up and demands things. She’s very demanding. She doesn’t just turn up and humbly go, “Uh, excuse me — do you have any food?” She turns up and says, “Where’s the fucking food? What the fuck is going ON here?” Very amusing but very demanding — they have grand presumptions that they’re always gonna get fed.

IE: Who is “Baby Poe”? In the chorus, it sounds like everybody in the neighborhood — even the lorikeets — dropped by to sing on that one.

SK: I don’t know if you’ve noticed this — and The Beach Boys took it to its logical conclusion — but every now and again in the ‘60s, you’d hear these records that were just really exciting. As soon as the song comes on, it comes on with this feeling of excitement, and when you listen carefully, there’s sort of like a little party going on in the studio. So I wanted to capture that idea. And I guess “Baby Poe” is a little poet. She’s like a little Chinese poet.

IE: And “Lillian in Cerulean Blue”?

SK: A ghost. Baby Poe, who really exists, saw Lillian one day in this flat that I’m living in and said, “There’s a ghost here called Lillian,” and immediately, I was touched by that idea. And in certain lights under certain conditions, I think you can see the former inhabitants of where you’re living at the time.

IE: Given that you’re probably sensitive to otherworldly phenomena, have you ever been in contact with anything like that?

SK: Yeah, I have. I have. Aliens and ghosts both. And gods and spirits. I’ve seen a lot of things in my time, and I am sort of sensitive to things like that. Sometimes I can walk along a row of houses, and if it’s very quiet and the conditions are right, I can stop in front of a house, and the stories of that house will leak out, and I can kind of feel them. It’s a very tentative thing. It’s not like a telephone call where this happens, and that happens — I can just sort of feel emanations from things. For sure, because that’s how I write songs. I guess I’ve got a thin skin, but if you’ve got a thin skin, of course, you can’t turn it off when you don’t want it. So if somebody says, “Your album is rubbish,” that really hurts me. I’ve got that thin skin that lets things in, but it lets everything in. But if you want to have thick skin, I don’t think you’re going to be a very good songwriter because you’ve got to pick on the very minutest of details. You’ve got to really be able to perceive minute and imperceptible things.

IE: After all the close calls I’m sure you had in your drug years — ditto here, full disclosure — do you ever feel, well, chosen to be here still, doing what you’re supposed to be doing?

SK: I have felt that something has been looking out for me. And my brother used to say to me, “Man, you’ve got the luck of the devil.” But sooner or later, that can’t go on. Sooner or later, that has to run out. I fell asleep once at the wheel with my children in the back, and I was driving in Maryland, on the Northeast coast of America. I fell asleep at the wheel, one foggy, sleepy morning, and I ran off the road. And if I’d run off the road five seconds before or five seconds after, we all would have been killed, because there was a huge ditch, we would have gone down into the ditch, the car would have overturned. But I ran off in this one place where there was a little side road that you could have run off, and then the car was brought to a halt by hitting all these tiny trees that thankfully slowed the car down. So I woke up with everyone in the car, screaming. But if it had been a fraction of a minute before that, we all would have died. So what were the chances of THAT happening? And yeah, I was a junkie for ten years, and I never OD’ed, and I never died. So just all my life, I have felt a hand…I really believe in a guardian angel. I really believe in that. I believe in all these things. I believe in angels, I believe in gods, I believe in spirits, I believe in devils, everything.

And I really have felt lucky, like something has been looking out for me all my life. And one day, I was in New York, and I was all hot and bothered about something, and I took a step into the traffic, and a hand restrained me. And a moment later, a huge bus zoomed by, right where I would have stepped. And I turned around, but nobody was there. And nobody was there. But yet a hand had restrained me, and I felt like that has happened to me time and time again. And obviously, one day, that hand won’t restrain me, and I’ll walk into the bus the way it’s meant to be. But I do feel like there’s something out there looking after some of us until it’s time for us to go.

-Tom Lanham

Category: Cover Story, Featured, Features