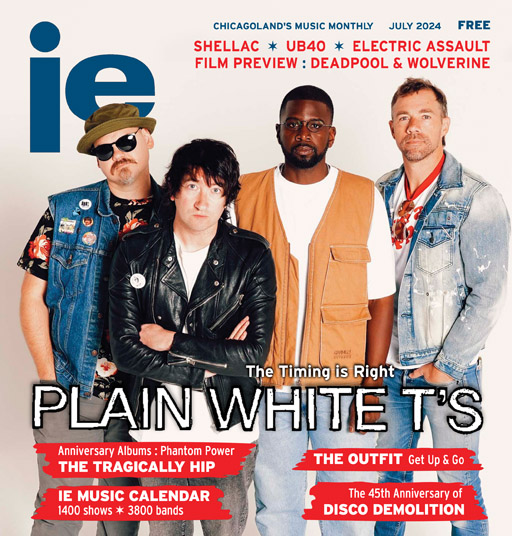

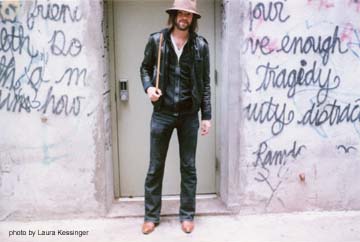

David Vandervelde interview

David Vandervelde

Back To Front

In a storybook world, David Vandervelde’s Chicago-to-Brooklyn-to-Nashville wanderlust would make him the ideal Dylanite troubadour. Sprung from the clutches of Holland, Michigan, he would crush our feeble intellects with a slapdash, rustic urbanity and cut a straight path through the hyper-media mire, grooming himself for a biopic to premiere in 2053.

In a storybook world, his recent dismount on Music City would be the third record-industry fortress he conquered in a blanket siege; he’d glide gallantly up Nashville’s booby-trapped, gilded staircase and sever the Interstate 40 escape route to Los Angeles.

In reality, our swash-buckling hero just thought it was time to find a home, someplace to put his feet up and maybe store some gear.

“I finally feel non-homeless for the first time in a while,” he reports. “I totally like New York, [have] nothing against it other than things are so expensive. I didn’t have any studio setup or even a practice space because I couldn’t afford it. My girlfriend, she was in magazines and doing a lot of super-long hours. She wasn’t feeling the whole magazine thing anymore, [so] we ended up choosing to move. We found a house and went for it.”

If only Vandervelde would see the potential in his story and put the music second. Here’s someone on whom, while spending most of his time in Chicago at Jay Bennett’s Pieholden Suite Sound Studio, the thought of crafting a dynamic debut album hardly dawned.

“I was 19 when all that was done,” he says of The Moonstation House Band (Secretly Canadian). “I wasn’t on Secretly Canadian yet or playing shows. I was a studio hermit all through high school and pretty much the entire time I lived in Chicago. I was recording music all the time. When we moved out of the studio I wanted to release something — I didn’t know what, necessarily. I wasn’t recording an album per se; I was recording songs that were all over the place, song to song.”

So what did he do to rise with the road and finally meet up with the zeitgeist? Brooklyn? Perfect! The streets of Williams-burg crawl with out-of-work musicians dying to be involved with someone whose debut pulled a 7.0 on Pitchfork.

But the expenses tied him down. He wrote songs in his apartment. On an acoustic. The swagger of the T. Rex-hometapes Moonstation was put in further jeopardy when he came back to the Midwest — Champaign to be exact — and laid Waiting For The Sunrise down in mostly one take.

Vandervelde explains, “Most of the stuff came from a demo session we did last July. A bunch of the people who play with me on the road just came into a one-room studio at a friend of mine’s place. We laid most of the stuff down demo-style, but kept it as the record. I liked it, did a couple overdubs here and there, but the big chunk of it is from that live session.”

“A couple overdubs here and there,” he says; if so, the man is Jesus and his overdubs are the two fish and five bread loaves. No waiting stalls Sunrise. Vandervelde claims to have had only tangential knowledge of T. Rex when he recorded Moonstation, maybe so. But the hands of Fleetwood Mac and George Harrison gently nudge this ’70s AM-radio breezebox out to sea. Opener “I Will Be Fine” could survive alone on its electric-piano textures yet has a bridge and chorus to push it over the top. Every time he seems to reach for ELO grandeur, Vandervelde pulls back just slightly — a skill he learned from Bennett, whose mentoring gets a nod with the “California Breezes” co-write.

“That has been sitting around for awhile,” he acknowledges. “It was one I started to play live and I called Jay up, ‘Hey, we recorded a version of it for the record. Is it cool with you if we use it?’ He was totally into it. That’s the old, old gem.”

It’s as if he went to sleep in 1975 and woke up today free from information-age pressures: hanging around the studio, no rush to push a record out, analog warmth, Jackson Browne on the stereo. Vandervelde is so retro-ly infected he even took a job with a local estate-sale auction house that deals with a lot of antiques. (One consolation: it’s online.)

“I went through a lot of different phases,” he attests, “but the records I grew up on were like most other people my age or who had parents my parents’ ages: Motown, The Beatles, The Stones, Fleetwood Mac. One funny thing I picked up on — never having put a record out before — was working on the one-sheet [promotional biographies for media and distributors] with the label and listing influences and that. The one-sheet for the first record definitely said ‘reminiscent of T. Rex and some Bowie.’ [I thought] people would listen to one song and decide I’m some huge T. Rex fan, when in reality I don’t own a T. Rex record. Maybe it’s a vocal thing. I heard T. Rex after I had been recording and doing stuff a certain way. It was like ‘Holy shit. Whoa.’ It’s mainly the quiet, double-vocal and the tape-pitch stuff.”

Some of that survived transfer to Sunrise, on tracks that presaged his eventual move to Nashville in a manner he couldn’t have predicted. Both “Hit The Road” and “Old Turns” channel the dark sessions that produced Big Star’s scarred Third/Sister Lovers. “Cryin’ Like The Rain” dips the Marc Bolan effect underwater, and it reemerges as George Harrison disguising a broken heart. Despite the occasional loose shard — Neil Young’s spirit breathes a fiery solo during “Lyin’ In Bed” — the album wafts like a reverie and ends with a similar lack of closure, floating away.

“I have a way,” he explains, “and maybe on Moonstation it was more of an obvious approach, of each song being produced, like writing a song to have a very distinct vibe, with the production going along with it. All of the songs for that record were recorded analog by myself, and it was experimenting with pitching the tape way up and making my voice sound crazy with effects, and varying the speed. With this record, kind of because of the situation I was in, I approached it naturally.”

Hence the decision to record live, though, keeping Sunrise from turning into a bar-band burner. Vandervelde worked against the grain of the typical debut/sophomore dynamic. Artists usually craft their first albums over years of trial and error, coming forth with their best songs having honed them over myriad shows. Follow-ups get written and recorded in short order, which is why they might pale in comparison while hitting many of the same notes. Vandervelde had no conception of a debut album, so Sunrise synthesized on its own.

“Yeah, I would agree,” he says. “Most of the songs were written well before they were recorded. I was playing guitar and singing those songs all the time in my apartment for a year before recording. I knew which songs would be on the record before doing it. It’s definitely a different approach from the first record, which was scratched together.”

The boy who works backwards . . . yes. It’s a tad cerebral, but this could be a storybook yet.

— Steve Forstneger