Sweet Home: November 2011

Timbuktu To The Delta

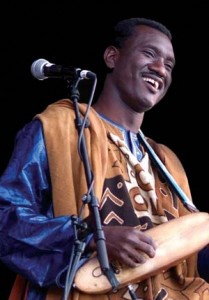

The ngoni, the kora, and the balafon may not sound like familiar instruments to most Americans, but for blues fans, these ancient African musical instruments hold the keys to the rhythms and traditions that developed into what we love. In the enlightening new book, From Timbuktu To The Mississippi Delta (Cognella) by Paschal Bokar Thiam Ed.D, the landscape of the blues is unraveled, starting with ancient African empires along the Niger River and journeying to the banks of the Mississippi.

“The tonalities of the blues is found all over West Africa,” says Thiam. “The elements and architecture that makes blues music possible is in West Africa. The funny tones that Europeans called blue notes, the syncopation, the vocal expression of instruments – that all came out of Africa.” The twisted path that follows the singular musical culture of West Africa to the shores of the U.S. where it is transformed into game-changing hybrids like jazz, gospel, and blues, offers a fascinating glimpse into African and American history and culture. Thiam, a noted jazz musician and professor of French and Senegalese heritage, uses the book to explain the complex connections between the two cultures with engaging detail.

In the introduction, Thiam explains that as a foreigner, he was always puzzled by how the dance moves and musical expressions of America closely mirrored West African aesthetics rather than the European sensibilities that would match the heritage of the majority of this country’s population. Examining the history of what he calls “cultural amnesia,” he states that he wrote the book to “look at the West African musical contributions and standards of aesthetics that have formed the music and the culture of the Mississippi Delta, in an effort to bridge this cultural and academic gap born out of a culture of indifference promulgated by former colonial institutions, out of respect for the unimaginable suffering, and in memory of the millions of West Africans taken from their native lands for a period approroximating 350 years, and whose children paradoxically and intuitively created in the United States, drawing from the depths of their collective souls, the rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic foundations of the musical traditions of the Mande, as expressed through the sonic landscape of the field hollers and work songs, the gospel and the delta blues, America’s only indigenous art form, jazz.”

At 155 pages with plenty of photos and illustrations, From Timbuktu To The Mississippi Delta supplies an engaging read. Opening with a chapter that explains the culture of West Africa and continuing with sections on medieval West African empires, African cultural concepts, and the “Rhythmic Intuitive Creativity” of the blues, the book demonstrates exactly how the essence of the blues and all of its related genres were nurtured in West Africa and then developed in the U.S.

The ancient African empires of Ghana, Mali, and Songhai were the cultural, academic, and social foundations for much of the artistic expression that would later develop in the New World. Spanning from 650 through the 17th century, these sprawling civilizations boasted powerful cultural influence that developed the standards of aesthetics that would travel with the West African populations who were transported to North America during the Atlantic Slave Trade.

“The city of Timbuktu [in Mali] is the center in common for all of the empires,” says Thiam. “The music of the king of Mali was sung everywhere. Western scholars don’t know what to call it; they call it blue notes. The link is between the Mississippi Delta, where thousands of West Africans were transported during the slave trade, and Timbuktu, which is the only place that people would hear these musicians play those notes.”

Those blue notes were played by djalis, intricately trained musicians and oral historians who performed with ngonis, a lute-like instrument; balafons, which are similar to xylophones; and koras, or African harp. The repertoire of the djalis in 11th-century West Africa consisted of melodies, fixed tonalities, and vocal expressions that bore an eerie resemblance to American blues.

“If you want to hear something close to the blues, you go to West Africa and then you will understand where John Lee Hooker comes from,” says Thiam. Indeed, his book draws such a clear line between West African cultural expression and American blues that it seems silly that there has ever been any question about how the genre was formed. It’s widely acknowledged that the music grew out of the suffering of African-Americans toiling in the South, but rarely does any research go beyond that. Thiam underscores the heritage of the blues both culturally and historically.

“Blues is an extension of an expression of West African elements. Albert King’s ancestors aren’t from Indianola, Mississippi, they are from Africa and they gave him his abilities,” he says. In terms of the battle within contemporary blues for acknowledgment and visibility of African-American blues musicians, Thiam belives that the battle has already been won. “Music is an expression of cultural power. When people play the music that you make and when they shake the way that you shake, you’ve won.”

— Rosalind Cummings-Yeates

Category: Columns, Monthly, Sweet Home