Stage Buzz: Q&A • Devo at The Riviera Theatre • Chicago

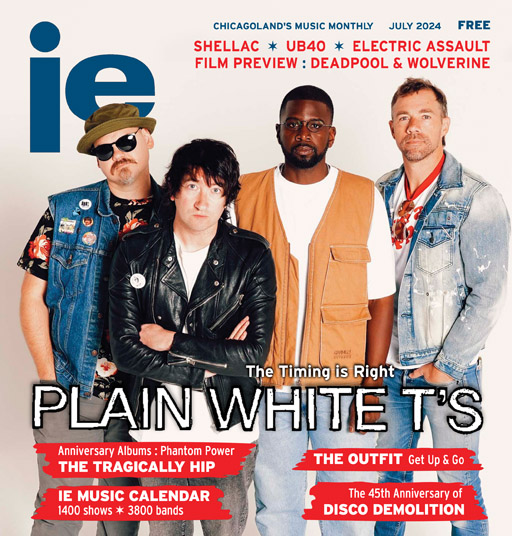

Devo. Photo credit: Courtesy of Devo. L-R: Gerald Casale, Jeff Friedl, Mark Mothersbaugh, Josh Hager, Bob Mothersbaugh

Stage Buzz interviews with Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh of Devo

Q&A by Jeff Elbel

Art rockers and New Wave pioneers Devo have chronicled the backward steps of humanity for more than half a century. Songs including “Peek-A-Boo!” and “Beautiful World” are slices of energetic synth-pop with wicked twists below the surface. De facto theme song “Jocko Homo” caps its manifesto for a devolved society with the H. G. Wells-quoting call-and-response chorus, “Are we not men? We are Devo.” The band’s Celebrating 50 Years of De-Evolution Tour visits the Riviera Theatre on Saturday, May 11.

Illinois Entertainer’s Jeff Elbel spoke to Devo co-leaders Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh in back-to-back phone interviews, posing many of the same questions to both men. Bassist and singer Casale spoke from home while preparing for travel with the band.

IE: Devo’s introductory singles perfectly established the band musically and thematically. Can you describe what “Jocko Homo” is, and why that was prime subject matter for one of Devo’s first singles?

GC: “Jocko Homo” became our namecheck song, right? This idea of de-evolution started as a literary and visual concept at Kent State University with myself and my colleague Bob Lewis. It kind of spilled over into the musical application. I started saying, “What would de-evolutionary music sound like?” That’s about the time I met Mark. He was younger than me, and he was taking classes at Kent State from professors that I had already had as an undergraduate. I was a graduate student at that point. I had been talking to one of my professors for about a year, bending his ear about de-evolution, found this pamphlet called Jocko Homo Heavenbound: King of the Apes. It was basically a fundamentalist, kind of Calvinist, right-wing repudiation of evolution and man’s being a sinner. There was a drawing of a stairway up to the devil, and each stair had a different sin on it, like the road perdition.

[The professor] knew that Mark and I were starting to play songs together. So, the pamphlet inspired the song “Jocko Homo.” Mark had this kind of odd, progressive rock riff that wasn’t in two-four time and started laying the lyrics over it from the pamphlet. He then started changing them and added, “Are we, not men?” from the film Island of Lost Souls, which was a ‘30s horror movie that Bob and I had been big fans of, and then Mark saw it. It all came together. We worked on it for three or four weeks, honing it and playing it in a basement of a house that [Devo guitarist] Bob Mothersbaugh and I rented in Akron, Ohio. Mark came over, and we were working on it there over and over until we liked how it was sounding. That’s how “Jocko Homo,” the namecheck song, happened.

IE: Were you synthesizing artists like Captain Beefheart and Kraftwerk for that sound, or were other bands your icons at that time?

GC: We had all kinds of influences. Certainly, Captain Beefheart was an influence. Kraftwerk, not so much because we had just discovered that Kraftwerk even existed. “Jocko Homo” congealed in early ‘75. Before that, we had written maybe 20 songs that were more like the songs you hear on Hardcore Devo – songs like “I’m a Potato,” “Can U Take It?,” and “Subhuman Woman.”

So, [“Jocko Homo”] was a growth. This was moving into new territory where proof was in the pudding. You hear “Jocko Homo,” and you go, “That doesn’t really sound like anything I’ve ever heard.” That’s what we were after. We wanted to get rid of our influences where [Mark] came from progressive rock, and I came from blues. I was in a blues band called 15-60-75, this locally famous band called The Numbers Band. We had played around Kent, Akron, and Cleveland. [Devo] got rid of all that. We started tabula rasa. “Jocko Homo” was proof of concept.

IE: The companion piece is “Mongoloid,” a provocative song that has attracted its share of flak. I’m not unsympathetic toward people who are aggrieved by the term, but I generally think the wrong people are offended by that song. It forecast the central premise of Idiocracy by three decades.

GC: Well, they misunderstood what was going on there. In “Mongoloid,” we’re attacking the people that made fun of so-called mongoloids. And you’re right, Devo’s worldview basically was Idiocracy way before Idiocracy. When I saw Idiocracy, I thought, “That’s the movie Devo could have made.” I’d like to think I would’ve done a better job of making it. The script was better than the movie, but certainly the point of view on human nature was right on point.

IE: Devo returns to Chicago on May 11th. I have heard differing things about your plans for the band post-tour. When this tour started last year, some reports called this a farewell tour.

GC: That tour was supposed to be like a 50th anniversary tour. Then, promoters wanted to latch on to make it a farewell tour, probably to sell more tickets. There was nobody steering the boat. If it’s farewell, it’s farewell to the first 50 years of Devo. Where do you go after that? What does devolutionary music sound like going forward? I’m not sure. I would certainly like to be proactive and make that happen.

IE: Your vision for the next 50 years could be “suburban robot” Devo, touring heads-in-glass-jars Devo, or holographic avatars.

GC: It should be all of that. Your songwriting tools could include self-imposed AI where you use AI to inspire you, and then you go back and mutate the AI that you used. Pick and choose and edit and let it be a springboard, where it’s a new tool as much as sequencers were a new tool in 1980.

IE: Have you tried it yet?

GC: Oh, yeah. Everybody’s been playing around with that for a while. It mostly is amusing because it spews the most kind of baroque and pristine cliches in the world with absurd lyrics. It’s amusing, but it’s a bunch of mediocre dreck. You have to get better at your prompts. Then as I said, you have to go back as an artist and actively pick and choose and mutate what it’s fed to you. Make it inspire you as a springboard for a new idea rather than accept the sounds and the progression it gave you. It’s a ridiculous amalgam of cliches.

IE: That’s a promising line of conversation. I loved the Something for Everybody album to pieces, so the idea that a tenth album is a possibility is good news.

GC: If it was up to me, it would already be out. I loved Something for Everybody. I just think because all these record companies were tanking, Warner Brothers failed to bring that album to market. When people hear some of those songs, they really like them. I did manage to hear songs like “Fresh” and “What We Do” on several radio stations out here, and they popped. You’ve got to understand, we were working with Greg Kurstin before he became a big deal. Greg Kurstin is a great producer, and I really like many of the songs on that record.

IE: “Please Baby Please” has never been performed?

GC: No. I would love to do that.

IE: Fingers crossed for someday. I wondered what it was like for such an intentionally provocative and art-focused band to have such a major hit with “Whip It.” Did that allow you to gather a bigger tribe of people who identified with issues that you cared about? Or did it gather more people who enjoyed the sound while they ignored the message?

GC: It’s always a double-edged sword, you know. Certainly, commercial success allows you more opportunities, and you also have funding to pursue some ideas that you weren’t able to afford before. At the same time, your message, whatever that may be, gets watered down. I remember this famous interview with Bob Dylan where the interviewer asked, “Doesn’t it bother you that people don’t understand what ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ is all about? He said, “No. If they did understand, it wouldn’t have been a hit.”

IE: Devo is particularly adept at the subversive song. You have material that sounds uplifting or encouraging on the surface but then lands a gut punch. “Whip It” seems to be on the level by comparison, even though it does co-opt motivational slogans in a satirical way. If you want things to improve, you need to take action.

GC: That’s true. Even though I was making a parody out of Horatio Alger and the cliches that you grow up with – “you’re number one, there’s nobody like you,” American exceptionalism – I was also inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow, where he uses those things and makes up these limericks in the book. I was so inspired and amused by ‘em I thought, “I’m going to do one.” That’s how the “Whip It” lyrics came about. But, of course, there has to be some earnestness in it. You do have to, at some point, take action and deal with the 800-pound gorilla in the room.

IE: I have a paragraph on a formative event. I hoped you would confirm or debunk it. Here goes: “Devo traces its history to the early ‘70s at Kent State University in Akron, Ohio. Art students Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh collaborated on projects with an underlying idea that society had ceased to progress and had entered a phase of regression. The infamous 1970 shootings by the National Guard during a student demonstration galvanized and catalyzed the pair’s art as a form of protest.”

GC: That’s pretty much true. I was a member of SDS [the anti-Vietnam War activist group Students for a Democratic Society] at that time. The May 4th protest was very thought-out and focused. It was about the fact that Nixon had expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia without an act of Congress. This was back at a time when people were still respecting the three rails of government and the separation of powers, and [were angry] that he had usurped that and become this authoritarian president. It sounds too familiar today, right? But there was outrage then, because people were pretty conversant with the Constitution and the way things were supposed to work. The fact that he had done that without an act of Congress was a big deal to any student of politics and to the general population that bothered to read newspapers and pay attention.

And so, to quote an old country song, we didn’t know the guns were loaded. We had no idea that it was not just a ritualistic protest, and that it would end in shooting and the death of unarmed students. I was in the middle of it. The students that were killed were behind me. They were further away from the guard. I think the guard was about the same age as us, and they could see us. We weren’t wearing gas masks, and I don’t think they wanted to kill people they could identify. So, they kind of shot over our heads. A lot of the people that were killed were just collateral damage. They weren’t even activists. So that traumatized me.

I probably had PTSD, because I remember just sitting down in the grass and feeling like I was going to vomit or pass out. I could see the blood running out of Jeffrey Miller down the sidewalk. I was shaking head to toe and just ruined for months.

IE: I appreciate you answering the question and regret that it’s something you’ve had to talk about for 50 years.

GC: Had that not happened to me, I don’t think Devo would exist. I changed after that. Until then, I was just Mr. Nice Guy, pseudo-hippie, live-and-let-live, and not fundamentally angry at the hypocrisy and intolerance that lies under the facade of the American dream. Let’s put it that way. Where you start to feel like everything you’ve been told is a big lie. Everything you know is wrong, and you start reevaluating. That made its way into my art and then the music. When I met Mark, he felt pretty much like me. He felt pretty disenfranchised and scared of toxic patriotism gone wrong. It made its way into the early songs.

IE: The way Devo is presented on stage is part of its appeal and the way you send messages. I thought about the Beatles by comparison. They wore matching suits in the early part of their career. Even though they abandoned the matching outfits when they made what I think is their most interesting music, I still remember those images. They’re etched in my memory. But the Beatles didn’t rip their tailored suits to shreds during every show. Does Devo’s use of things like matching hazmat suits and energy domes serve a symbolic purpose to help target a message? Is it a parody of conformity? I hoped to hear your logic about that.

GC: It’s ambiguous and ambivalent, because there’s a certain power in presenting yourself as a unit where you’re more than the sum of your parts. The individuals become a meta entity, one step removed from reality, almost like comic book characters. But we were not trying to look good. The Beatles were trying to look good. We were trying to look almost off-putting or Dada. We were wearing plastic-coated paper suits that were meant for workers to wear when they’re spraying dangerous chemicals. We were presenting ourselves in a way that was shocking people at the time. Since we were design students and artists, it also helped project a graphic image to the crowd. We would limit our lighting to three colors, and we would coat the stage with black plastic and wear the yellow hazmat suits and only be hit with bilious green or purple light. It really was this minimalist, in-your-face, polarizing aesthetic. And we loved that.

IE: You used different matching suits to present the Something for Everybody material, but I thought that approach heightened the impact of a song like “What We Do.” On the surface, it seems like a song about industry and ability, but underneath it’s a song about meaningless routine, consumer culture, or control through conformity.

GC: It’s almost like the fifth Devo rule: “We must repeat.” What we’re saying is humans are just stuck in a rut and they just do this. It’s like, eat, sleep, defecate. Eat sleep, defecate. Eat sleep, defecate.

IE: It’s likely a coincidence, but I have to ask. I read one of your biographies saying that society had basically “Peter-principled out.” That was from 1982, circa Oh No! It’s Devo. I know the Peter principle about rising to one’s level of incompetence, which is a very devolutionary concept, but I’d never read the book. I found the first paperback printing from 1970 online. The original title typeface has bold red letters stacked in a way that looks just like an energy dome. Had you seen that before?

GC: You know what? It is a coincidence.

IE: Just an interesting intersection, then.

GC: I had never even thought about that. Very astute. [laughs]

IE: If Devo claimed in 1982 that society had basically Peter-principled out, there are many who would say you’ve been proven disastrously right. Still, I imagine the effect has been more severe than you had imagined.

GC: It’s not funny anymore. Let’s put it that way. There was always a satirical sense of humor in Devo’s aesthetic, and now, it’s dire. What we’re seeing is the implosion of reason, logic, tolerance, even the ability to critically process information. We live in a society where you’re being inundated and drowning in disinformation and propaganda beyond what we could have ever imagined. People repeat slogans and take sides mindlessly like a mob.

IE: Bias confirmation is indulged.

GC: Absolutely. You’re watching this naked march towards fascism, and the media acts almost like it’s a big game. They’ll openly report what the game is, what people are doing, and the tactics they use, almost just like they would report football plays. The point is, it’s really happening.

You have a Supreme Court entertaining the outrageous idea that a president, no matter what his criminality is, should have absolute immunity, including assassinating political rivals. You’ve got these guys in black robes entertaining it, theoretically arguing – as if there’s an argument. You’re going, okay, this is it. We’ve done it. It’s The Handmaid’s Tale meets Kafka.

IE: It’s alarming. Our bastion of impartial sanity is dysfunctional.

GC: And the Supreme Court’s beyond the law. They’re not elected. There’s no term limit, and they’re not going away. No matter how ridiculous and patriarchal-authoritarian, and retrogressive their positions are, that’s going to stick.

IE: We could talk about that for an hour. I’ll move on. A long time ago, you talked about reading Popular Mechanics and seeing visions of the gleaming future with domed cities, flying cars, and with everybody groomed and fed. The utopian future of technology has gone awry. Barring what you said about AI as a tool for creativity, there’s plenty of media-projected fearmongering suggesting that it’s preparing the Skynet takeover of humanity. Nonetheless, AI is the frontier of technological development and advancement.

GC: I certainly understand the dark-side possibilities of AI. Given human nature’s propensity towards fear and evil, the downside of AI is probably predictable just like the atomic bomb was predictable. Except this time, AI may decide that humans are a nuisance.

IE: Let’s talk about your new documentary film Devo. Does Chris Smith’s authorized Devo film capture your story in the way that other documentaries have not managed to do?

GC: There really hasn’t ever been a real Devo documentary at all. When you look at just the depth and breadth of the material that he could draw from to try to distill Devo down to an hour and a half meant that you had to leave most of it in the bin. What you’re getting is kind of one director’s impression of the elements that made Devo Devo. It’s the Cliff’s Notes version of Devo’s story.

IE: We’ll look for the five-hour director’s cut someday.

GC: To me, it would’ve been nicer as a series. That’s the way you could have shown the context both historically and aesthetically of what Devo is really about and gotten into some of the real meat. Whereas this is a breeze-through.

IE: Does it get the essence of Devo? Are you happy with it serving the purpose that a 90-minute documentary can serve?

GC: Yeah, exactly. It does that.

IE: My introduction to Devo was strange. As a kid, I tuned into Solid Gold one day expecting pop music accompanied by sexy dancers in leotards but saw Devo performing “Peek-a-Boo!” with a maniacal clown. It was terrifying, but I couldn’t look away. I thought of Devo as scary but fascinating, which seemed to suit your intentions.

GC: Yeah. It was supposed to be kind of scary.

IE: Something I think that the band does especially well is making a song that seems encouraging or positive but then lands a gut punch. “Beautiful World” is an example.

GC: Sure, that’s my favorite, where you wait for the punchline. It’s nakedly true. That’s me singing and writing the lyrics. It’s one man’s opinion. It’s a beautiful world for you, but not for me. And I made a video that showed why.

IE: The video points to the obliviousness of the suffering of others. Is “That’s Good” looking at the “greed is good” mentality?

GC: Not really. It’s tongue-in-cheek and there’s a couple lines that take it that direction, but it’s not.

IE: Other songs do seem to be genuinely encouraging, even if there’s some underlying criticism. We talked about “Whip It,” and there’s “Time Out for Fun.” There’s the idea behind it of corporate oppression and rat race drive, but on balance it just seems like a pretty good recommendation.

GC: I like the spoken intro on “Time Out for Fun.” I hear it now and I go, God, that’s amazing, because it’s broad enough that it could be talking exactly about now. It doesn’t date itself.

IE: I can think of at least one song that’s directly on the nose. “No Place Like Home” seems like a song for this very moment.

GC: When I wrote those lyrics, I thought about a follow-up to “Beautiful World.”

IE: Am I overlooking another ecologically themed song from the back catalog that I would connect to “No Place Like Home?”

GC: Possibly not. I know that around Total Devo, I was talking a lot in interviews about the ozone layer being eaten away. We even made a poster where we’re posed satirically on a talk show in chairs, and we’re discussing that with text subtitles.

IE: “Later is Now” leans into the underlying urgency.

GC: “Later is Now” definitely gets to it, but I’m thinking about earlier in the eighties. “Some Things Never Change” touches it, too.

IE: I think you’ve said that without Devo, you may have continued your graduate studies and become an art professor. Has your career allowed you to be someone who actively provokes thought the way an educator would, anyhow? Or are you just a devoted agitator?

GC: Since I was headed toward being an art professor, I suppose that kind of educational zeal made it into Devo’s aesthetic. Yeah, it probably did.

IE: So, Devo has put in 50 years, and you’re not finished yet. You’ve at least got to stay on the job until the new shift arrives. I wondered if we’ll see another band that blends art, politics, wit, and music to the degree that you have. In the past, the Residents would have been an example, albeit without the political component. Midnight Oil would have been an example, without the art aesthetic. Is there anyone to pass the torch to? I wondered whether a band like Devo could emerge today.

GC: I’d like to think it could. I don’t like to be a pessimist. It would be interesting. What would the Devo of today be? What would they be doing? They wouldn’t look or sound like we did, but they would have their own programming and their own YouTube channel. If Devo had had the tools that people have today, we would’ve just created a whole media empire starting small and would have gone directly out to the world the way people do with video podcasts.

IE: It wouldn’t be brought to you by Warner Brothers. You’d have to go find it.

GC: I just don’t see anybody engaging on that multiple-level thing where they’re socially involved, they’re audio-visual artists, they’re a lifestyle entity, they have a narrative … I don’t see it. They could do everything. They could have a brand that’s not just a silly brand. It could touch every medium. And like you mentioned in the beginning of this interview, they could have a whole world where there’s avatars themselves that live on. People could enter that world and interact with them.

IE: It makes you wonder whether the circumstances of student protests happening now could impact an embryonic Devo – not that I would wish that kind of tragedy you witnessed upon them. Bands like Pussy Riot have come out of protest movements, but they don’t have the same reach or technological/arts component.

GC: Imagine if somebody was as popular as Taylor Swift but also had a potent message. [The powers that be] would be in trouble.

Interview with Mark Mothersbaugh

(Singer and keyboardist Mothersbaugh spoke from his studio Mutato Muzika in Hollywood, California.)

IE: Devo’s introductory singles perfectly established the band musically and thematically. Can you describe what “Jocko Homo” is, and why that was prime subject matter for one of Devo’s first singles?

MM: It was at ground zero of what we were calling Devo, and it was the first lineup of the band that was Devo when we did our single on Boogie Boy records. It was Jim Mothersbaugh and drums, Bob Mothersbaugh on guitar, Gerry Casale on bass, and I was playing synth. It was a little more radical than what we ended up doing when we went to Warner Brothers and Virgin Records. We kind of pulled it back one notch. If you look at the first video with those four people and listen to that, Jim was an early pioneer in electronic rhythm instruments. He built that drum kit. He had a day job at, I think, Midas Muffler, and he welded together the frame that held the practice pads that he hit. They had acoustic guitar pickups attached to them, and then they went into fuzz tones and Echoplexes and ring modulators and things like that.

So, if you listen to the sound on “Jocko Homo” and “Secret Agent Man” on that first film, it’s different than what we sounded like later. That was a little more radical electronic. When Alan [Myers] joined the band and Bob Casale started playing, we had five of us in the band. At that point, we’d paid attention to what was going on in New York and London. We loved the Ramones. We started playing our songs faster because of them. Before that, we sounded sort of like Captain Beefheart meets Sun Ra meets an Italian sci-fi movie.

That was cool, but it was hardcore. We got paid to quit a show one time.

IE: What a great story. It may not have been as funny in the moment.

MM: Well, we thought if we’re pissing these people off, we’re doing something right. That’s how we took it.

IE: As far as the subject material of “Jocko Homo” goes, the H.G. Wells quote became the band’s call-and-response theme.

MM: “Are we not men?” Yeah, Island of Lost Souls. That was the original film [in 1932]. There were two remakes, and they were never as quite as good as the original one with Bela Lugosi and that whole crew.

IE: Fortunately, we can still find that at the library. H.G. Wells was my first favorite author as a kid. I remember reading The Island of Dr. Moreau before I knew there was a movie.

MM: Yeah. Good stuff.

IE: Devo returns to Chicago on May 11th. I have heard differing things about your plans for the band post-tour. When this tour started last year, some reports called this a farewell tour.

MM: Booking agents had the idea that it was a good selling point if they called the shows that we did last year a farewell tour. They come up with those phrases, not the band. But we liked being able to slice it into a 50-year segment. We spent 50 years talking about de-evolution, humans being out of touch with nature, and maybe it was our fault things were going out of control on the planet. Unfortunately, too much of that came true.

IE: It was distressingly accurate.

MM: We were supposed to be just kind of negative and critical. We were hoping we weren’t right.

IE: It’s not so much satire anymore.

MM: Quite honestly, I’m hoping there is still Devo going forward from these shows in some shape or form. This stuff in May is kind of the tail end of those shows we’ve been doing that were all part of the 50-year anniversary kind of thing. And I don’t know, but maybe Booji Boy is right. At our last shows, he’s been saying, “Think of this as year one for the next 50 years.”

So, 51 to 100. He’s saying that everybody agrees with us that humans may have caused the biggest problems that we have here on the planet and that we’re the ones out of touch with nature. But he’s saying, “Now is the time to mutate, not stagnate.” We have all this misinformation we’re exposed to on a daily basis, but kids are smart. They do research. They know how to use the internet better than adults do. They grew up with the internet, so it’s a part of their DNA. I just feel like the right thought process is to say, okay, things are messed up. How do we fix it? How do we change it?

I don’t think humans are ever going to become cavemen again. I think we’re closer to cavemen now than we will be in five years. I think things are going to change at increasingly rapid speed. It’s pretty exciting,

IE: There’s potential windfall and potential threat, perhaps in equal measure.

MM: Just kind of keep the cavemen away from atomic weapons and things like that. There are amazing possibilities for the future.

IE: Your vision for the next 50 years could be “suburban robot” Devo, touring heads-in-glass-jars Devo, or holographic avatars.

MM: There are a lot of possibilities. I hope I’m not too late to have my cranial and bodily information transferred to an electronic device. It could happen. Tim Leary was hoping for that. I was friends with him when he was in his last years. He really wanted to be preserved. He was already showing me AI things back before he died. He was showing me early AI that was a therapist. You would type questions and it would type things back to you and ask you questions. It was the very beginning of that kind of thing with computers. I think he saw the possibility and he wanted to be frozen. It was too chaotic around him and there wasn’t enough consensus. He wasn’t really verbalizing it properly for the people around him that were all grabbing at him constantly.

IE: But he wanted to see what came next.

MM: Yeah, he was up for it.

IE: Given that Devo could continue for another 50 years and beyond, may there be a follow-up to Something for Everybody? That was a great record. You’ve got nine studio albums. 10 would be a nice round number if you don’t consider albums to be obsolete.

MM: For the last couple of months, I’ve been having people send me their AI versions of Devo songs. For 50 years, I’ve listened to people do their own versions of Devo songs. There are so many of ’em that I’ve heard, and I’ve just gone, “Why didn’t we think of that? That’s great.” There’s a lot of stuff like that out there. I don’t have a response to the AI stuff yet other than it makes me laugh. I find it amusing.

IE: It’s interesting to think of “Dare to Be Stupid” by “Weird Al” Yankovic as a precursor to AI versions of Devo-style songs. He assembled a set of Devo tropes into his homage, and AI automates that process.

MM: I prefer Nirvana’s cover of “Turn Around,” if I get to choose, but I’m curious to see where human creativity goes next. Remember the time where humans were worried about cars getting in the way of horses and buggies?

IE: They were a nuisance that impeded everyday useful activities.

MM: Exactly. They were turning things upside down. What’s going to happen to livery stables? The guy who shoes horses is going to go out of work! I love what’s happening with AI, or at least I think I do.

IE: There’s plenty of media-projected fearmongering suggesting that AI is preparing the Skynet takeover of humanity, but what you’re saying is true. As a creative tool, we can barely imagine what could come from it.

MM: I see it more as something that frees people to deal with their intellectual ideas. It’s wonderful that somebody’s learned how to play the violin well enough to be in the Chicago Symphony. But what if kids had those powers already? Where would they take art next if all those things become something that you don’t have to spend years and years learning? I like the idea of finding out where it’s going to go.

IE: It’s interesting to think that in hundred years someone might look back on the beginning of AI and think it’s as quaint as the car replacing the horse. Maybe could be frozen like Timothy Leary wanted to do, so we could come back and find out.

MM: Or maybe instead of frozen, we could just get transferred into devices. We have these little vehicles that deliver pizza and groceries that run up and down the street. My studio has been on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood where all the clubs were from the sixties into the eighties. Now there are these little things that are delivering food that mingle with us. I’m sure our machinery will be a little more sophisticated than that. I don’t know how old you are, but I’m turning 74 next month. There are days when I get up and I think, I wouldn’t mind an electronic entity right now.

IE: I’m turning 58, so I’m not that far behind.

MM: Your body’s still in denial. Don’t worry, it’ll be in full shock soon. Or else things change through technology, and you avoid ever having to be in your seventies.

IE: I wondered what it was like for such an intentionally provocative and art-focused band to have such a major hit with “Whip It.” Did that allow you to gather a bigger tribe of people who identified with issues that you cared about? Or did it gather more people who enjoyed the sound while they ignored the message?

MM: When we started, we were purposely looking for sounds that we hadn’t heard before. We were looking for ideas that weren’t popular. We wanted to have an effect on pop culture. Because of the beat and the sound of “Whip It,” it opened Devo up to a much wider audience. And I think you could look at that as a creative success.

When we first started with Warner Brothers, we were thinking, “Why do we want to go to a record company?” We decided, well, that’s how you become more than the Ohio version of the Residents. I was a fan of the Residents, but we didn’t want to be the Ohio version of them. I thought we had a big idea and thought it’d be amazing if we had a chance to bring it to a bigger public. “Whip It” allowed that to happen. There were people that became interested in the song merely because it segueway-ed well with whatever else they were dancing to in the clubs. It had lyrics that weren’t specific, so people could make out of them what they wanted to. But it did lure people in to then go, “What do they mean by swelling, itching, brain?” It was a success at subversion, inspired by Madison Avenue.

IE: Devo is particularly adept at the subversive song. You have material that sounds uplifting or encouraging on the surface, but then lands a gut-punch. “Whip It” seems to be on the level by comparison, even though it does co-opt motivational slogans in a satirical way. If you want things to improve, you need to take action. I can appreciate it as a gateway to get people to consider the messages in other songs.

MM: From a Club Devo point of view, it was a successful song.

IE: I have a paragraph on a formative event. I hoped you would confirm or debunk it.

MM: Sure.

IE: “Devo traces its history to the early ‘70s at Kent State University in Akron, Ohio. Art students Gerald Casale and Mark Mothersbaugh collaborated on projects with an underlying idea that society had ceased to progress and had entered a phase of regression. The infamous 1970 shootings by the National Guard during a student demonstration galvanized and catalyzed the pair’s art as a form of protest.”

MM: That sounds about right. That was the time we were there. The FBI has photos of when I marched with SDS [the anti-Vietnam War activist group Students for a Democratic Society] down to the recruiting station. My brother Bob was in high school. I remember my mom crying when FBI agents came over to the house and showed her pictures of him trying to stop firemen from putting out the fire when students lit the ROTC building on fire. She was crying and going, “Not my Bobby!”

IE: That’s a traumatic formative experience to have gone through.

MM: Well, I didn’t get along with anybody from kindergarten through 12th grade. I fought with other students and with teachers. I got to Kent, and all of a sudden, I was not only anonymous, but they had an incredible art program at the time. I got introduced to all sorts of things I wasn’t aware of. Morton Subotnick came on campus and performed, and I got to stand in the room with him while he was playing synth. I saw movies. I’d never paid attention to music in movies until I saw Satyricon and heard Nino Rota’s abstract score where he relied on historic and ancient instruments to create the sounds, and the score was so important to the film. I got introduced to printmaking, and I just flipped over that. That was about as high-tech as you could get in those days as far as an artist was concerned. I’d just wait for people to leave class at 3:30 in the afternoon, and I’d have the whole art department to myself and the print-making room. I could print four colors, burn screens, clean screens, print, and then do the next color. And then, at night, when I was finished, I was kind of a pioneer post-up artist, sort of like Shepard Fairey and Obey, just 30 years earlier. That’s how Gerry and I met.

IE: If you had such trouble through 12th grade, was it a lucky thing that you went to college at all and found yourself there?

MM: It was a fluke that I went. My grandparents on both sides were coal miners that had come to Akron during the Depression just to find a job in a factory so they could feed their families. There was never any talk about college. I had a schoolteacher at my high school who had entered my artwork in county art shows. I’d gotten first place a few times for different things I’d done. I doubt that they have it anymore, but there was a program with Kent State at the time. Students in any category, whether history or English or whatever, could show some reason why they should go to college but didn’t have the funds. Without telling me, this teacher put my name up, and I got offered a partial scholarship. I was like, “Oh, I could get a job at night and pay off my college. This is amazing.”

Honestly, my main reason for going was I didn’t want to become 1-A [for the military draft]. I just thought, you know, I can’t think of a single Vietnamese person I want to kill. They could wave whatever flag they want. I thought if communism isn’t as good as democracy, that sucks, but I wouldn’t want to kill somebody because of that. So, I jumped at it when the teacher told me I had a chance to college. College turned my whole life turned upside down in a great way. Everything started. I felt like I had a clean slate, and I had ideas.

There were great teachers at the school at the time. I came in at a really lucky time. That’s why everybody felt brave enough to protest the war in Vietnam. We felt like what we do and think does matter. What we say is important. We were taught differently by the governor. It became a threat to him, so he swatted us down. But that just gave me more things to think about.

IE: I should ask about the new documentary. Does Chris Smith’s authorized Devo film capture your story in the way that other documentaries have not managed to do?

MM: When you are the center of a documentary, there’s always going to be things that make you think, “Why didn’t he talk about this?” A documentary is one person’s vision of somebody else. Chris used to be in a Devo cover band when he was a kid, and this was his take on it.

IE: In 90 minutes.

MM: Yeah, in 90 minutes. The reality is that if you did a documentary on Devo, I’m sure it would be different than his. If I did or if Gerry did, our documentaries would be different than Chris’s. But it’s enjoyable, and it’s all good information.

IE: Do you feel respected and validated by it?

MM: Yeah. He put a lot of things on the screen in a 90-minute time period. If that’s someone’s introduction to Devo, that could be an interesting introduction. I saw something on the news the other day, and it was somebody in Bon Jovi talking about a Bon Jovi documentary. They were saying, “It doesn’t have everything I would put in it.” I just chuckled, thinking, “What is in it?”

IE: The way Devo is presented on stage is part of its appeal and the way you send messages. I thought about the Beatles by comparison. They wore matching suits in the early part of their career. Even though they abandoned the matching outfits when they made what I think is their most interesting music, I still remember those images. They’re etched in my memory. But the Beatles didn’t rip their tailored suits to shreds during every show. Does Devo’s use of things like matching hazmat suits and energy domes serve a symbolic purpose to help target a message? Is it a parody of conformity? I hoped to hear your logic about that.

MM: We thought of Devo as a machine or a unit on stage. We were turned off when bands went from being “The Animals” to “Eric Burdon and the Animals.” They changed something. We were not about a bunch of individuals on stage. We liked the idea that we were a working entity that blended together. We were all bigger than just one person in the band. We still do that.

IE: So, Devo has put in 50 years, and you’re not finished yet. You’ve at least got to stay on the job until the new shift arrives. I wondered if we’ll see another band that blends art, politics, wit, and music to the degree that you have. In the past, the Residents would have been an example, albeit without the political component. Midnight Oil would have been an example, without the art aesthetic. Is there anyone to pass the torch to?

MM: Well, it’s funny you’re saying that. When we were first trying to decide what Devo would be and how we would be – this was before Menudo – we thought, Devo doesn’t have to be the four of us. It could be other people. We could send three or four Devos into the world at the same time. We could just stay here and come up with the music and the videos and the ideas and the costumes and design the show. We wouldn’t have to hang out in these clubs or theaters. That could be someone else’s job.

IE: Like Brian Wilson, when he retired from touring with the Beach Boys and stayed home to work in the studio where he liked it.

MM: See? Okay. I never thought of a connection between Devo and the Beach Boys. That’s kind of funny. So, we could easily let go of being the ones on stage, to be honest with you.

IE: You could franchise it like McDonald’s.

MM: Yes, but a different kind of McDonald’s. Maybe one that would have better information.

IE: A subversive kind of McDonald’s that’s actually good for you.

MM: Right, exactly.

IE: I read one of your biographies saying that society had basically “Peter-principled out.” In other words, it had risen to its level of incompetence and could go no further. That was from 1982, circa Oh No! It’s Devo. Four decades later, I imagine the effect has been more severe than you had imagined.

MM: We’re turning into Idiocracy.

IE: The song “Mongoloid” forecast the central premise of Idiocracy by 30 years. Now, we experience it in real-time.

MM: Things are happening a little bit faster than what we were thinking back then. I read a book when I was 19 in 1969, called The Population Bomb. It was by a sociologist who basically said humans are the species that’s out of touch with nature. We’re eating up everything. We’re destroying all of nature. He predicted that by the year 2050, nature would retaliate against humans with a virus that would kill off humans but save the planet.

IE: He was off by 20 years.

MM: He took a lot of flak for that. There were people going, “Hail man, we are the center of the universe. You’re an idiot. We deserve everything.”

IE: I suppose it’s that or “The planet is impervious.” That makes me think of “No Place Like Home,” the last song on what is currently the last Devo studio album. That song doesn’t seem like satire. It has no surprise ending. It’s in your face and relevant right now. Hopefully, there will be more to come.

MM: I like that song. We’re in that situation now where we’re a legacy band. People aren’t really coming to see Devo or other legacy bands so that they can hear something new. “Hey, Keith and Mick were hanging out and they decided to write a new song!” Nobody cares about that. They want to hear “Get Off My Cloud” and “Street Fighting Man,” songs that meant something to them when they were growing up. I don’t know what band you grew up with that made a difference to you, but you want to hear the songs that band did that take you back to when you were thinking the world is insane, and then that album helped you feel like maybe something’s okay.

IE: It’s true. At the same time, I like to think I’m not as unique in this mindset. If I’m this invested in a band, I want to know they’re still alive and doing what made me love them, which is creating music. I’ll certainly love hearing Devo play “Whip It.” I also imagine that since you’ve played it countless times, you may not be as excited by it as me. On the other hand, I’d be excited to hear a great recent song like “Human Rocket” or hear something announced as “the first single from our new album.” I take your point that that’s not the prevailing concertgoer, but I can’t be alone.

MM: All I’m saying is with a legacy band, there’s a different reason for being there. I’m the one who would like to do a new album. My brother [Devo lead guitarist Bob Mothersbaugh] also works at Mutato Muzika also. I keep sending little things to him to see if I can lure him into putting some guitar parts on some stuff. He’s avoided me so far in the last six months, but we’ll see what happens.

IE: His guitar work on Something for Everybody might be my favorite that he’s done. That record has a great presence of guitar while still being synthesizer-forward.

MM: Yeah. I kept pushing electronics for the source of finding new things, but Bob and Alan and Gerry’s bass playing really held the sound of us together and kept us from floating too far off into the Sun Ra galaxy.

IE: My introduction to Devo was strange. As a kid, I tuned into Solid Gold one day expecting pop music accompanied by sexy dancers in leotards but saw Devo performing “Peek-a-Boo!” with a maniacal clown. It was terrifying, but I couldn’t look away. I thought of Devo as scary but fascinating, which seemed to suit your intentions.

MM: [laughs] Yeah, we scared people. I hope we didn’t scare you too bad.

IE: I’ve recovered from the trauma well enough to speak with you today. Experiencing that song led me to other songs like “Beautiful World.” Even before seeing the video, I realized that it was uplifting on the surface but had a darker twist about being oblivious to the suffering of others and things like that.

MM: Yeah, right. I think the video is maybe the most successful part of the song. I really love the video.

IE: Thank you, Mark. I look forward to seeing the show next weekend in Chicago.

MM: I’ll be wearing a red hat.

IE: Easy to spot. I might be wearing a red hat, too.

MM: Okay. I’ll be looking for you, then.

This Q&A was quoted in the May 6, 2024, printed edition of the Chicago Sun-Times.

Appearing The Riviera Theatre Saturday, May 11, 2024 @ 7:30 PM

Tickets: axs.com/events/532372

This Q&A was quoted and appeared in the May 6, 2024, print edition of the Chicago Sun-Times.

Category: Featured