CinemaScopes Review: The Beatles: “Get Back”

Peter Jackson’s three-part docuseries begins with a backstory montage that brings us from 1956 to 1969. Let’s encapsulate just one moment in that timeline that became the defining moment for the Beatles as it was for millions: February 9, 1964. This particular date fell on a Sunday. Americans had gone through their weekend routine that would lead to the family circling ’round their black and white televisions in anticipation of The Ed Sullivan Show, a weekly version of England’s Sunday Night at the London Palladium.

There was always a magical aspect to the Sullivan show, and after Sunday’s ‘day of rest’ etiquette, everyone in the family seemed extra eager to be entertained. This was especially true in February 1964 – only 11 weeks after the utter turmoil caused by John F. Kennedy’s assassination. Collectively the country was ready to feel good again. As the time approached that particular Sunday night and the show was coming back from commercial, no one in the world, especially the Beatles themselves, could have predicted that their American television debut would catapult them into the very fabric of the American experience. American teenagers were utterly blown away by the fact that their extraordinarily original music was penned and performed by the boys themselves. The Beatles had already become a phenomenon within the time it took to toss a Brillo pad into the kitchen sink. Their look, clothes, hair, boots, voices, harmony, guitars, drums on such a high pedestal, impossibly cool accents, and undeniable charisma burned into our collective memory banks and culture.

Americans had been amazed at the sound they had heard on their AM radios from this new British group when their song “I Want To Hold Your Hand” hit the airwaves in November of 1963. The song was first heard when DJs across the country began to play imported copies of the single after Capitol Records had refused to release the single in America (it was already Number 1 in Europe). The Beatles made a pact: Their dream was to come to America, where all their songwriting mentors and performing idols were from, but they didn’t want to come over until they had a Number 1 hit in the charts. Capitol Records finally relented and released the song on December 26, 1963. The Beatles became America’s Number 1 group on the Billboard charts before even setting foot on American soil.

Fast forward to 1988’s Rock’ N Roll Hall of Fame Induction ceremony where Mick Jagger refers to the Beatles as “The Four-Headed Monster.” I loved that analogy – as you’d never see one without the other three. That’s the kind of camaraderie, collective charisma, and sheer power the world’s first rock group had, and how impossible it seemed for all the other rock bands to compete with that. The British had officially invaded the American music industry.

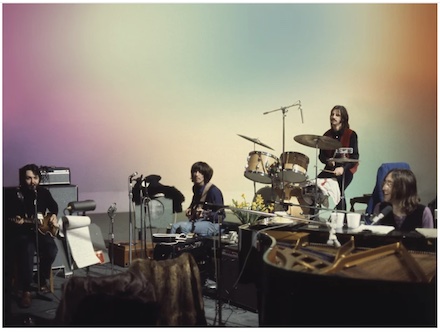

Peter Jackson’s The Beatles: Get Back is a revelation. It’s a validation. And it’s a complete marvel. The three-part docuseries is a study of the creative process. Whether you are a rabid fan, an intermediate observer, or one of the uninitiated, you can’t deny the sheer talent that permeates the film where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Composers are, by nature, a second-guessing lot. Many are constantly asking themselves, “Is this good enough?” followed by “It’s not good enough!” followed by the endless tinkering as they posit, frame, mold, cut, collapse, and join melody, harmony, and rhythm together in ways that seem at once ordinary and extraordinary. To witness the Beatles chasing the same things that we are, and in the same way, are stunning moments within the film that validates what we do as creatives. Observing their inner circle in such an intimately-exclusive way – the proverbial fly on the wall – is like having a master class in composition, lyricism, arranging, production, and direction simultaneously. The duality of album creation and film creation happening concurrently and in the hands of masters is at once captivating, fascinating, overwhelming, and emotional. Props go to Michael Lindsay-Hogg for shooting all the footage in his cinéma verité style. Peter Jackson is the first to acknowledge it; Lindsay-Hogg’s footage, originally shot for the maligned 1970 Beatles documentary Let It Be, gives the heart and soul to the docuseries.

In 1968 the Beatles were reportedly pitched the idea of starring in a film adaptation of The Lord of The Rings by then Apple Films executive Denis O’Dell. And as you might imagine, Paul was slated to play Frodo, John would play Gollum, George was to portray Gandalf, and Ringo, of course, would be Samwise Gamgee. The idea was stopped in its tracks by Tolkien himself, who would not allow the rights of his story to go to a group of pop musicians that he didn’t like. It’s probably a good idea it didn’t get made, but it is undoubtedly a serendipitous irony that Peter Jackson eventually makes The Beatles: Get Back.

After the backstory sets the stage where the Beatles are as they begin the final year of their groundbreaking decade, the first thing that grabs attention in Part 1 is the complete absence of voice-over; there are no cinematic edits or cuts to a narrative, as you are simply in the room with the Beatles. For a musician, let alone a composer, this is an absolute dream of a position. The only semblance of a narrative would be the occasional sentence or two of text appearing on the screen to underscore a point or set up the following sequence. I found myself instantly realizing how special this was. Not only is the music creation itself breathtaking to watch, but the entire process of their banter, their endless goofing-off, their evident love for each other, and how they supported (and at times – didn’t support) the music that is happening live. The Beatles led the world in creative pop-rock output within the previous three years. Their super imaginative ability to overdub and bounce tracks over multiple 4-track machines joined together to create the most sophisticated albums.

The band then discusses how they want this next album and accompanying film to show them simply creating the songs in the studio, rehearsing, and ultimately performing 14 songs live on stage. Their last live performance was at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 1966. They collectively decided to “retire from such nonsense” as the rigors of touring, and the constant lack of proper audio gear (such as the now-essential ingredient of stage monitors) got old fast. They are constantly spitballing as to where this climatic location of the live TV special will be: Lindsay-Hoggs’ favorite is to do a grand finalé with the Beatles performing live at an amphitheater in Tripoli; “torchlit in front of 2,000 Arabs!” The lads were not too keen on this seemingly absurd idea. Then suggestions keep bringing them back to the Twickenham film studios where they have begun this writing workshop and rehearsal; dark, dank-yet-colorful, but ultimately too cavernous and impersonal.

The first significant takeaway happens as we witness the genesis of a Beatles’ song coming together out of thin air. The song is the iconic “Get Back.” Paul has approached John when realizing that the goal they have set for themselves – creating 14 new songs in 3 weeks – has put extraordinary pressure on them. Since they began their residency at Twickenham, they haven’t made much headway in that regard. Until they do, on the morning of their fourth day at Twickenham, and while awaiting John’s arrival, George and Ringo hold back yawns as they are listening to Paul with his trusty Hofner bass in hand, trying to get something going. He is unconventionally playing his bass; he’s playing an actual chord on the bass and strumming it like a guitar, giving him more of a background and a vibe that references the rhythm section of a band, with the semblance of a drummer. The rhythm created will clearly become that of Get Back, but the amazing thing is that the song doesn’t exist yet – we are clearly witnessing its birth. McCartney is humming and singing some nonsense syllables as he centers around a single note that will soon become “Jo Jo,” over and over again, until he adds two more notes to his melody, which then unleashes the lyrics that suddenly appear, and the song magically now exists, wherein two minutes previous, it did not. Brilliant. A good place to note is that The Beatles could NOT read or write music. They were running on pure instinct, playing by ear, literally. This further mystifies their untouchable success. Musicologists have cited the Beatles for their incredibly successful songwriting abilities and powerful melodic writing, specifically with none other than Maestro Leonard Bernstein, claiming the Beatles are at the head of the class when it comes to popular music. He repeatedly saw them as endlessly inventive and never resting on their laurels.

The conclusion of Part 1 culminates in George announcing quite casually that he’s leaving the group; Lennon immediately quips “when?” and Harrison replies, “now; see you around the clubs.” The action has occurred due to the long-standing “Harrison vs. Lennon and McCartney“ battle for song inclusion within their albums. Earlier, the famous ‘row‘ from the original Let It Be film shows where Paul admits that he often feels he is nothing more than an annoyance to George. Harrison is so tired of having his ideas brushed off by the Lennon/McCartney alliance that one can’t help but feel empathy for the clearly talented George. He has no collaborator, and he’s late to the songwriting game. He asks if they would like to hear a song he has come up with the previous evening and begins to play what ends up being the very well-regarded Harrison/Beatles classic, “I Me Mine.“ McCartney’s body language response is instant; he immediately walks over to George, leans over to look at his lyric and chord sheet, and begins contributing ideas. Shortly after that, John almost immediately interrupts his playing and singing with rude quips such as “just run along, son, see ya, we’re a rock n roll band ya know, boom ba–boom ba-boom ba–boom ba–boom.” This really startles George. Disgusted with Lennon’s reaction, George announces, “now, John, I don’t care if you don’t want it, I don’t give a fuck, it can go in me musical.” This was the last straw for George. With the tension still brewing, it was just time for him to make his departure announcement. And when Georges does (and was so cavalier about it), McCartney is stunned. For the first time in the film, we see tears welling up in Paul’s eyes as he contemplates if this will be the end of the band. After George walks out, Lennon doesn’t take much time to retort, ‘we’ll get Clapton.‘ But then, as Peter Jackson’s on-screen text reveals, the three Beatles decide to persuade George to rejoin the group by having a group meeting at Ringo’s house. Although the forum doesn’t go well, a subsequent meeting brings George back, apparent as Part 2 begins.

With the reunification of George, the Beatles decide to leave the impersonal Twickenham studios for the more intimate and familiar surroundings of their eclectic Apple headquarters, located in the stylish Saville Row section of London. We see the basement at 3 Saville Row morph into an ad hoc, temporary recording studio. The moment we see the Beatles in this new environment, the attitudes and moods of all involved are significantly elevated; it’s a fresh start. Ironically, Paul is easily seen as the musical director and taskmaster here. Until John met Yoko and their relationship solidified two years earlier, John was always the group’s clear leader. But once John & Yoko became a thing, that relationship is where he placed all of his attention, much to the chagrin of the other three Beatles.

Original Let It Be director Michael Lindsay-Hogg had placed microphones in the commissary at Apple, so we get to hear candid conversations between John and Paul for the first time discussing George and how close they had come to breaking up. Peter Jackson obtained new technology that could isolate audio that couldn’t be five decades ago, enabling us to become flies on the wall (or, in this case, in the flower pot). An old friend of the Beatles is in town and stops by the studio to say hello – keyboardist Billy Preston – who they initially met back in their Hamburg days when Billy was playing with Little Richard (where the Beatles and Preston had become good friends). Incredibly, they had just been talking about needing a keyboardist on almost every one of the new songs, potentially including Nicky Hopkins, who played piano on Rolling Stones records. Having Billy there and inviting him to check out the brand new Fender Rhodes electric piano that has turned up proves to be that bit of magic sauce the Beatles so desperately needed.

Now reinvigorated, it’s fascinating to witness their creative process in action once again. Billy’s presence has put them on best behavior. John, apparently overcome with excitement that Billy Preston has walked into the studio at George’s invitation when a keyboardist is so badly needed, immediately explains to Billy how they are looking for a keyboardist and that he would be a perfect choice if he’s interested. John also adds that he’ll be on the album if he’s game. Can you imagine? The first tune they hit is “I’ve Got A Feeling,” a song we had heard at least three times before when the group was putting it together. Now, Billy instantly comes up with the electric piano riffs that we recognize will make it to the finished recording. The fit is so prolific and perfect that the Beatles’ enthusiasm is evident; huge smiles abound. We notice now, even more than before, how the sublime chemistry of their songwriting chops mix with their individual and collective charisma to form a song creation platform that is simply astonishing to behold. They finish each others sentences, figuratively and literally, as if telepathy is at play. The moment the song is over, John moves close to his microphone, looks right at Billy, and says, “You’re in the group!” The Beatles are thrilled, Billy is delighted, and we viewers are ecstatic.

Toward the end of Part 2, the Beatles had abandoned the idea of traveling to some exotic location to perform their final concert due to George being adamantly against it. Director Lindsay-Hogg and engineer/co-producer Glyn Johns come up with an exciting concept for the last show. We witness Lindsay-Hogg and Johns approach McCartney and whisper to him their vision: Play live on the roof of Apple headquarters during the lunchtime break to capture this sudden, unexpected concert by the world’s most famous rock group. Jackson zooms in for an extreme close-up shot in slow motion, brilliantly showing the utter joy on McCartney’s face as he realizes the beautiful mix of avant-garde meets-rock ‘n roll meets insane surprise. And it’s all done silently, with only Peter Jackson’s text telling us what is being shared privately with Paul. It’s a ‘goosebumps on your goosebumps’ moment.

The final installment is entirely about their preparation for and execution of the rooftop concert. As opposed to the way we saw the rooftop concert on the original Let It Be film, we get to see the entire show this time and experience the Beatles and their entourage evaluating it afterward in the control room. The bonus is that we see so many of the songs that ended up on the Beatles’ “final” album, Abbey Road. A common misconception is that the album Let It Be was the Beatle’s final effort, but it was primarily recorded nearly nine months before Abbey Road.

After all the highs and lows, the intense laughs coupled with the acrimonious tension, the walkouts, the goof-offs, the brush–offs, the procrastinative apathy, and the unbridled enthusiasm of Billy Preston–as–catalyst, it is such a payoff. It’s somewhat ineffable to pinpoint fully, but it is clear that the rooftop concert experience was emotionally cathartic for the Beatles, their entourage, the Londoners who were there, and us as the viewers.

I firmly believe this transformative docuseries will go down in the history of music documentaries as the quintessential, penultimate take on the creative process as seen through the eyes of the most prolific and influential popular music group the world has ever known. It’s extraordinary, astonishing, and consistently breathtaking to be a fly on the wall as we witness the sheer joy, camaraderie, talent, vision, conflict, crisis, splitting apart, and coming together of the Beatles. Observing their inner circle intimately is like having a master class in composition, lyricism, arranging, production, and direction. The duality of album creation and film creation happening concurrently and in the hands of masters is at once captivating, fascinating, overwhelming, and emotional. Discovering the Beatles were secretly the world’s greatest cover band was astounding to witness. How many times did they suddenly burst into yet another classic rock ‘n roll tune from the ’50s – as the direct result of their “internship” in Germany where they performed in Hamburg for eight hours a night, seven nights a week?

The Beatles – with the help of producer George Martin, director Michael Lindsay-Hogg, engineer and co-producer Glyn Johns, Apple exec and longtime roadie Mal Evans, Apple Films director Denis O’Dell, and ancillary musician (and almost fifth Beatle) Billy Preston – all under the masterful leadership of filmmaker and storytelling giant Peter Jackson – have provided us with a masterwork on creativity and is a testament to the love this group of like-minded Liverpudlians had for each other. Their collective chemistry, charisma, talent, and intuition were second to none. Nothing could be more inspirational and validating for active creators who share the talent and desire to achieve. To the uninitiated, realize that what may appear as repetition or excessive length in rehearsals will begin to make sense the more you research the phenomenon of the Beatles. Thank you, Peter Jackson. Thank you, Michael Lindsay-Hogg. The Beatles: Get Back is a love letter to the creative process. We are the lucky beneficiaries of your shared, distinct vision – and we’ll be feeling the effect of your prolific film for decades to come.

So what becomes of the remaining 52 hours of footage? Perhaps Peter Jackson might steer away from his adventures in Middle-Earth (and other stories) long enough to have The Beatles: Get Back become an annual event; releasing another “season” of three episodes each year so that – if you do the math – we can look forward to 17.33 more years with Beatles’ ‘Getting Back.’ Surely, I jest, but with half-truths being what they are, Jackson has opened the floodgates. After experiencing this monumental achievement in 2021, Beatles aficionados, intermediate fans, and newbies alike will indeed look forward to more of the same (albeit in a “Director’s Cut” or “Super Deluxe Box Set”), etc. Jackson has reset the creative docuseries in a significant way. Forget the voice-over, the spoon-feeding; let the topics at hand – the players and the cinematography do its magic. Can you even imagine what it would be like to have our newly christened wall-fly status activated to witness the makings of Meet The Beatles, A Hard Day’s Night, Rubber Soul, Revolver, Sgt. Pepper or Abbey Road as they respectively came into shape? Peter Jackson’s transformative epic The Beatles: Get Back is most likely the only chance we’ll have to be in the same room with the most celebrated popular music writing team in history, observing their creative process and witnessing the birth of so many of their iconic songs. Many who give their undivided attention to these remarkable eight hours will come out the other end wiser for the wear; full of inspiration and insight.

The Beatles: Get Back is available now and streaming on Disney +

– Steven Kikoen

2 hours would have been plenty for the casual fan. Diehards (like me) loved the extended length, but I lost my son to football on night two.