Sweet Home: October 2011

Blues Passages

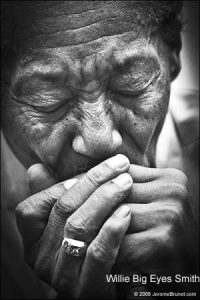

The last two months have packed powerful blows to the blues community, with the passing of David “Honeyboy” Edwards and Willie “Big Eyes” Smith. Both enjoyed significant careers that helped preserve the soaring legacy of the Delta blues. As elder statesmen who represented crucial decades of living blues history, they will both be sorely missed.

Edwards was a wonderfully illuminating spirit and the last living link to the first generation of Mississippi Delta blues musicians. There was so much skill and wisdom that flowed through his 96-year-old frame that his playing seemed divinely guided. He was noted for being the last connection to Robert Johnson. Honeyboy reportedly witnessed Johnson sip his last drop of poisoned whiskey, but he symbolized much more than that historic affiliation.

Born in Shaw, Mississippi on June 28th, 1915 to a talented guitarist and violinist for a father who worked as a sharecropper in Misissippi’s brutal system of subsistence farming. (His grandfather had been enslaved on the very land that they worked.) Edwards started playing guitar at 12 and by 14, he had left home to travel and perform with Big Joe Williams. His nuanced guitar playing was recorded by the Library Of Congress in 1942 and shortly after, he joined the Great Migration north and journeyed to Chicago. He played on Maxwell Street and street corners, in small clubs, and for the seminal Chess Records.

Besides his fretwork, Edwards’ shows were significant because of the evocative, biographical stories he told between songs. His astonishing memory would supply the finest details of his experiences riding the rails across the South and playing with notables like Sonny Boy Williamson, Son House, Sunnyland Slim, B.B. King, Charlie Patton and, of course, Johnson. His recollections became the basis for his landmark memoir, The World Don’t Owe Me Nothing: The Life And Times Of Delta Bluesman Honeyboy Edwards in 1997. A vivid mix of music history and cultural documentation, the book explores events like the Mississippi River Flood of 1927, the vicious reality of plantation life, lynchings, arbitrary vagrancy laws aimed at black men and the makeshift courts set up to put them in prison – all conditions that inspired the blues in its purest form. But Edwards never had any use for pity or blame; his story is told with honesty and appreciation for his singular life.

My favorite Edwards quote frankly sums up his opinion about the visibility of blues in contemporary society: “The blues ain’t never going anywhere. It can get slow, but it ain’t going nowhere. You play a low-down dirty shame slow and lonesome, my mama dead, my papa across the sea, I ain’t dead but I’m just supposed to be the blues. You can take that same blues, make it uptempo, a shuffle blues, that’s what rock ‘n’ roll did with it. So blues ain’t going nowhere.”

Sugar Blue, the noted blues harpist, composed a tribute to his legacy: “In observance of the death of Honeyboy Edwards, one of the last of the great Delta Bluesmen, I am reminded of the incredibly bountiful legacy that our fathers have left us, of the trials that they endured and the assault on their legacy by those that would steal the cultural heritage of our people. The blues witnessed the slave quarters where we knew the lash, in the shacks of tenant farmers who knew the backlash. Working from sun to sun, ‘sharecropping’ for slave wages or no wages, in a Jim Crow system that denied the equality promised by emancipation . . .

“Music made for the people by the people and full of laughter, love, loss and pain of Life’s day to day struggle to survive. This is part of my heritage in which I have great pride. Paid for in the blood, the whips, guns, knives, chains, and branding irons ripped from the bodies of my ancestors as they fought to survive the daily tyrannies in the land of the free, where some men were at liberty to murder, rape and lay claim to all and any they desired.

“From this crucible the blues was born, screaming to the heavens that I will be free! I will be me! You cannot and will not take this music, this tradition, this bequest without a struggle as fierce and bloody as the one that brought us in chains of iron beneath the putrid decks of wooden ships to toil in pain but not in vain!

“That is Blues Power.”

A tribute to Honeyboy Edwards will be hosted by Buddy Guy’s Legends on October 19th.

Willie “Big Eyes” Smith helped perfect the seminal Chicago blues sound. His traditional blues shuffle provided the foundation for many classic Chicago blues tunes and his drumming can be heard behind such notables as Muddy Waters, James Cotton, Bo Diddley, and Buddy Guy. At 75, he managed to create a second act as a blues harpist, which was his first instrument. Last year, it was his harp playing that snagged his and Pinetop Perkins’ Joined At The Hip a Grammy for Best Traditional Blues Album.

“He was one of the last living links to the golden era of the Chicago blues,” says Chicago blues harp master Billy Branch. “He was known as a great Chicago blues drummer but he reinvented himself as a harp player and won a Grammy! It was like a fairytale ending and I had the utmost respect for him.”

Smith was born in Helena, Arkansas in 1936. At 17, he visited his mother in Chicago and she took him to see Muddy Waters, which changed the direction of his life. He took up the blues harmonica playing with a trio until he switched to the drums after he began sitting in on Waters recording sessions in the late ’50s and in the band on and off from 1961 until ’80. He co-founded the Legendary Blues Band with Pinetop Perkins, Louis Meyers, Calvin Jones, and Jerry Portnoy soon after. Launching the second part of his career as a harpist, he and the band toured with The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and Eric Clapton and backed up John Lee Hooker in Blues Brothers. Smith was noted for his signature mix of soulful Delta rhythms layered with the Chicago blues.

— Rosalind Cummings-Yeates

Category: Columns, Monthly, Sweet Home

Thanks for the history lesson — hadn’t hear of Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, but I had the pleasure of meeting Honeyboy Edwards less than a year ago at the Symphony Center. Nice article.