Koroboro Rock

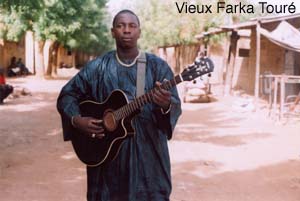

Legacy and familial inheritance has always played a significant role in African society. Whether dictating marriage, social position, or profession, the rules and expectations of family lineage have changed very slowly. And being the son of an internationally famous father does not help matters. This is the situation Vieux Farka Touré, son of late Malian guitar master Ali Farka Touré, faces with the release of his pivotal, self-titled debut. Not only must he address the huge Touré legacy, but also the expectations of his noble family and his country. It’s a super-sized order for a 25-year-old, but Vieux appears up to it.

Ali was Africa’s most celebrated guitarist. With searing, soul jangling riffs, he revealed the centuries-old source for pure Delta blues. His three-decade career brims with genre-defining albums such as The Source, which featured a blues homecoming collaboration with Taj Mahal, and the Grammy-winning Talking Timbuktu, which blew the lid off narrow world music categories by topping indie charts. Last year’s posthumous Savane was crowned a masterpiece and named best album of 2006 by rock and global critics alike. Despite all this, it was never easy for the elder Touré. Born into a famed noble family that traces its roots back to the royal family of the ancient Manding Empire, he was not encouraged to play music. A person of noble birth playing music in Africa was similar to a blueblood in the States becoming a janitor. So Ali had to fight to play music, struggling through the corruption of the music industry and battling to change traditional attitudes about musicians. Even with all his success, his mother never approved, and he rarely played in front of her.

Vieux carries all this history on his slender shoulders. If that wasn’t enough, he also fought to play his music. His father’s disillusionment with the music industry made him want another life for his son, so Ali forbade Vieux from becoming a musician. He played in secret until he was certain of the path he had to take. When he enrolled in the National Arts Institute in Bamako, a notable arts school where Habib Koite studied, Ali refused to pay for transportation. “There wasn’t cultural resistance, I just had to persist against my father,” says Vieux through a translator. “I wasn’t intimidated by my father. I just continued and persisted.”

It took years before his father relented and that was only after family friend and master kora-player Toumani Diabaté convinced him of Vieux’s musical gifts. Possessed of a soulfully nimble skill that echoes his father’s, Vieux’s sound embraces the foundation built by his dad while still reflecting fresh influences such as rai, Touareg music, and reggae. “My music is organic, it’s whatever comes to mind or my fingers,” he says.

Soaring and full of energy, he calls his music “Koroboro Rock,” which means rock from his Sonrai ethnic group. It’s an apt name because his 10-track CD literally rocks with the rhythms and essences of his Niafunke, Mali home.

Vieux Farka Touré (World Music) sounds like next-generation desert blues. Filled with proverbs and dedications to elders, including his father, as well as splashes of funky afro- pop references, it smoothly bridges the distance between old school and new school. “I started to walk this path when I enrolled in the Arts Institute, but I never really committed to it until I went into the studio,” says Vieux. “When we recorded the album, everything just came together.”

With a rough-hewn voice that belies his youth, Vieux guides listeners on the journey from the swaying blues guitar and njarka (spike fiddle) of “Dounia” to the skankin’ reggae beat of “Ana.” All the tunes are sung in Sonrai, Fulani, or Bambara but transcend cultural barriers with an emotional intensity that needs no translation. The CD also boasts Ali Farka Touré’s last recordings, a haunting father-and-son duet, “Tabara,” and a sizzling electric guitar rocker, “Diallo.” Diabate also makes an appearance, elevating “Touré de Niafunké” into sublime kora rock.

The elder Touré always insisted ancestral spirits bestowed him with his musical talents, and he performed the rituals and sacrifices that honored them, including placing fetishes inside instruments. Vieux appears similarly blessed, and although he belongs to a less superstitious generation, he’s taking no chances. “Vieux is touring with his father’s electric guitar from the ’50s,” explains the album’s producer and musician Eric Herman. “The jack was rusted and I took it in to be repaired. As soon as he heard that, Vieux stood at attention. ‘Make sure that when they change the jack, if they find anything inside the guitar, not to take it out.’ The fetishes give magical powers to whoever plays the guitar,” Herman says.

Magical powers or not, Vieux Farka Touré must forge his own legacy, even if it is on his father’s firmly laid path. “I feel pressure from all corners of the world,” he says. “Wherever I go, people say, ‘I knew your father and you have to do things that will do his legacy justice.’ But I will do what I feel is right.” His debut illustrates this belief clearly, with respect for his history and dedication to his individual interests. When asked what an African musician’s main role should be, he didn’t hesitate to describe the path that he has already undertaken. “An African musician should transmit the wisdom of Africa and its people, as my father did.”

– Rosalind Cummings-Yeates