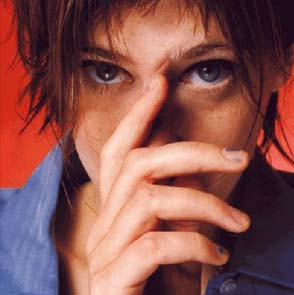

Beth Orton

BethOrton

Stranger Things Have Happened

Talk to musicians enough, and phrases reminiscent of sports cliches make their way to the fore. It only makes sense: we have our stock questions; they have their stock answers. Only instead of giving 110 percent or taking one game at a time, there’s “We really love coming to your town” and, drumroll, “I don’t listen to my records, but I can listen to this one.”

But Beth Orton is very convincing when she uses them. For all her lanky, runway model beauty, on the topic she shows a kind of clumsy sincerity, as if she doesn’t think you believe her and you absolutely must.

Comfort Of Strangers (Astralwerks), her latest, is an album she says had to be made; it practically made itself. “I think with each record I felt my spirit got more diluted. By the third record [Daybreaker, 2002], I think I was trying to please people; I wanted to please everyone. I had good intentions: I wanted to make it a combination of everything, but by doing that I think I was moving away from my center.”

Daybreaker, for the record, is a lovely album, but so was its predecessor, Central Reservation. But it was lovelier than Daybreaker, just as its own predecessor was the loveliest of them all. The meaning of this gobbledygook is she’s been tapering off — and she knows it.

“I think around the time of just finishing Daybreaker I just about had enough,” she says. “I was so frustrated and I had moved on in my mind, but not any other way. It’s very funny to keep touring a record that you . . . that you’ve moved on [from].”

In many ways Orton is lucky. Just about anyone could rifle off a list of five artists who lost their way after one album and never recovered, much less held onto a recording contract.

She says, “I found sometimes what I didn’t like was coming back to overdub the vocals and overdub stuff that really I would have liked to got more at the moment. And that sounds maybe like small things — to me it’s huge because it’s the spirit. I like being there with people and the moment, really. And I think that’s funny, but on the second record it was the same, and on the third record it was the same, and I was just like, ‘I don’t want to do that anymore!’ Even something as simple as that to me was kind of damaging the process. It didn’t bring out the best in my voice, it didn’t bring out the best in my character, in a way.”

So for Comfort she enlisted help. “First I wanted to produce it, and then I met another artist and thought, ‘Maybe I’ll co-produce it with them.’ But I found that wasn’t quite what it was. That to me meant I wasn’t concentrating on what I was good at and what I’m good at is writing songs. It’s words, it’s melodies. I think I had a vision — I had a dream, ha! — to see it through, and in the end what was wonderful was meeting Jim O’Rourke. He had the same vision, it was implicit. It was two like minds.”

This is the same O’Rourke who became one of the architects of post rock in Chicago, a temporary fifth member of Sonic Youth, and, as Chicagoans outside post rock recall, mixed Wilco’s Yankee Hotel Foxtrot in a way that ended the band’s relationship with Reprise. He seems a prime candidate if you, as Orton said, just want to concentrate on words and melodies. But where he goes with it, well . . .

“I didn’t want to get overproduced,” Orton explains. “I wanted to make a live record, you know. I wanted this record to be very live, very of the moment. I wanted it to be a bunch of musicians in a room, I wanted it to be analog, I wanted to hear the hiss and the hum of the tape and the buzz of the room. It’s funny: We just understood. He was like, ‘It’s about your voice. It’s about your songs, it’s about what best serves it. It’s pretty simple.’ And it was like,” trying to replicate her delight at his accord, “‘Yes! Right!'”

— Steve Forstneger

To learn more of how Orton and O’Rourke jived, grab the April issue of Illinois Entertainer.